The U.S. government took very aggressive action over the weekend to save the vast wealth of depositors at Silicon Valley Bank. That 40-year-old institution had become rather unstable of late as a result of rising interest rates that they failed to anticipate and invest in the kind of long-term, high-risk/high-reward vehicles responsible for the 2008 financial crisis, such as mortgage-backed securities.

Late last week, the bank's depositors, composed of bold, wealthy tech investors, as well as startup companies with substantial venture capital, began getting somewhat nervous about the bank’s ability to cover deposits above the $250,000 level, the amount which the FDIC insures for every account and that worry very quickly – in a matter of fewer than two days – turned into full-blown panic and then a bank run that prevented the bank from even coming close to finding the liquidity to cover the mountain of withdraws and transfer requests that poured in from very panicky depositors.

Over the weekend, at the urging of some of the most prominent Silicon Valley venture capitalists, the Biden Treasury Department announced that the U.S. government would ensure that all depositors would be made whole, no matter how much in excess of the $250,000 limit their balance was.

That move, surprisingly, has provoked a very vitriolic debate between people like, on the one hand, our guest tonight, Matt Stoller, of the American Economics Liberties Project, who insist that this is quite similar, if not in scope, then in kind, to the 2008 Wall Street bailout under the Bush and Obama administrations in which the U.S. government first acted to save the country's richest people who caused the crisis while the middle class and working class were about to suffer. And then on the other side, we have tomorrow night's guest, venture capitalist David Sacks, the first CEO of PayPal and a prominent venture capitalist who has been insisting that the problems at Silicon Valley Bank are not unique to that institution, but instead reflective of a systemic problem, and that without U.S. government intervention, not only Silicon Valley Bank but countless other regional banks would have failed quickly due to contagion, panic and other similar bank runs. We'll examine that debate by speaking first to Matt Stoller tonight and then to David Sachs tomorrow.

Plus, last night at the Oscars, Hollywood liberals did what Hollywood liberals and liberals generally love to do. They heaped praise on a film, “Navalny,” with the Academy Award for Best Documentary.

Now, Navalny, as you probably know, is the dissident – an opponent of Vladimir Putin currently imprisoned in Russia for that dissidence – and, in the process, these Hollywood liberals bravely denounced the abuse of a dissident by a faraway government who was an official U.S. enemy, i.e., Russia. In the meantime, these same people, as usual, ignore, if not outright support, their own government's ongoing years-long imprisonment of our own dissident: the journalist Julian Assange.

This is about far more than who wins some glitzy and increasingly pointless awards but it does say a great deal about how governments are able to get their own citizens – not just our government, but all governments – to constantly focus on the abuses of governments on the other side of the world, over which they exert no control. All of that means forgetting how their own government is doing the same, and often worse.

As a reminder, System Update is now available in podcast form. We are available on Spotify, Apple and most other major podcasting platforms. The episodes are published in podcast form 12 hours after we first air here, live, on Rumble. If that's your interest, look for that and follow System Update on those platforms.

For now, welcome to a new episode of System Update starting right now.

Monologue

So, in order to understand the debate that has been provoked by the Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen's announcement that the U.S. government would step in - as leading Silicon Valley venture capital has spent the last several days demanding that it do - and protect 100% - every penny - of all depositor’s funds in the now collapsing Silicon Valley Bank, as well as at least one other bank, that is also collapsing rapidly, – on which Barney Frank, ironically, the longtime Democratic congressman who, along with Senator Chris Dodd, authored the legislation after the 2008 financial crisis that was designed to prevent exactly this from happening again – as it turns out, Barney Frank happens to sit on the board of the bank that is the second bank to fail as part of this bank grab, meaning his legislation did not evidently fulfill its promise of preventing a systemic contamination and essentially threat of a financial collapse from happening again as it happened right under his own nose at his own bank.

Now, in order to understand the debate and it's a complex debate and one that requires expertise – which I am the first to acknowledge I do not possess, which is why we're going to have a guest on tonight who does, who has one view and a guest tomorrow night who also does who has the other – it's very important to remember and understand the 2008 financial crisis and the context of that debate, and that I do feel very comfortable speaking up because I covered it extensively at the time as a journalist involved not only with complex financial instruments, but also the political dynamics that shape our country.

That financial crisis was a long time in the making. It was something that people were able to predict and actually did predict. Increasingly, Wall Street was able to invest in very, very complex and opaque economic instruments that were highly risky and like all risky instruments, had a high amount of profit. They were able to invest in that because of the rollback, various financial protections that came in the wake of the Great Depression, in the early 1930s, that were designed to keep separate commercial banking activities – that are generally more conservative and risk-averse from investment activities that tend to be riskier. And the idea was to prevent a systemic collapse in the commercial banking sector that led to the Great Depression in the first place. And over the years, especially the Clinton administration and their genius economists like Larry Summers and Robert Rubin, right from Goldman Sachs, decided that these protections from the FDR era were obsolete and banks could be unchained in order to start to become much riskier. And they were heavily rewarded because the Wall Street sector and the banking sector began investing heavily in and funding heavily the Democratic Party as a result of its servitude to the banking industry. They had a lot of Republican support as well during the Clinton administration with all of these rollbacks, and that led to the ability of all kinds of banks with your money, depositor money, to be able to engage in much riskier types of investments. One of the investment schemes that they particularly liked was called mortgage-backed securities, which was when banks would offer loans to people to buy houses and would keep the houses as collateral. And the value, the very high value of the real estate market ensured that those mortgage-backed securities, which were all grouped together, had a great deal of value and could be traded as commodities. Unfortunately, when the real estate market and the real estate bubble collapsed, the value of those mortgage-backed securities collapsed with them. And that led to an unraveling, a very rapid unraveling, of almost all of Wall Street, starting in September and October of 2008. So, during the last several months of the Bush administration, when the Treasury secretary still was Hank Paulson, who before joining the Bush administration as Treasury secretary, had been the CEO of Goldman Sachs, very much of a Wall Street background and his argument was that we need to act immediately to save the financial markets with a gigantic infusion of credit and cash in order to protect the credit markets from collapsing.

What a lot of people don't remember is that the very first proposal that was negotiated between the Bush White House, as the 2008 presidential action and John McCain, was approaching with congressional leaders, including John Boehner, the then House speaker, and Nancy Pelosi, the then House minority leader and the head of the Democratic Party. Both of them were on board. The establishment wings of both parties were on board with Hank Paulson's plan to give a gigantic infusion of $800 billion into the Wall Street sector to prevent it from collapsing. The warnings were just as grave, in fact, way graver than the ones we're hearing now, that if the government doesn't immediately act to save these Wall Street institutions, the entire system will collapse. There will be bank runs, nobody will trust these institutions any longer, everyone will try and take their money out of the system and not just the U.S. financial system, but the global financial system will collapse.

That crisis was much greater in scale than the current one, at least so far, but the arguments are very similar. Obviously, there was a lot of resentment that the U.S. government was going to bail out the titans of capitalism after all. The whole idea of capitalism is the reason that you get rich is that you make bets, risky bets. And if you're right, you get rich. But that only works if you also then lose everything when you're wrong. And yet what happened here was they all made very risky bets. They got rich when they were right and then when they were wrong, instead of losing, which is the other side of capitalism, which has to be the other side of capitalism, instead, the U.S. government intervened, stepped in and said, “Oh, don't worry, we're going to back you up. We're going to give you a gigantic infusion of cash to prevent this system from collapsing”.

Even though it generated a lot of anger – why should the richest people in the world, who caused the crisis in the first place with their recklessness, be protected with taxpayer-funded money? – it nonetheless happened because the argument prevailed that if we didn't protect the richest people on the planet who caused the financial collapse, all of us would suffer because the entire financial system would collapse. And there was an infusion of $700 billion or $800 billion that was nowhere near enough to calm the markets. And then once President Obama was in office, he selected Timothy Geithner as his treasury secretary, who was most known for being an incredibly loyal servant to Wall Street. They infused a lot more money into Wall Street, and Wall Street and its casino went on. Dodd-Frank was the promise of the American people to say, we're going to reform everything so this never happens again. The argument was, look, these institutions are too big to fail. We cannot allow them to fail. We're allowed to watch them succeed and get rich when they're right. But when they're wrong, we can't let them fail. And that created a lot of resentment, political resentment. That first bill sponsored by Hank Paulson, was negotiated with John Boehner and Nancy Pelosi, the first time it came up for a vote in the House it actually failed, despite warnings that its failure would cause the implosion of the global economic system. And it failed because a majority of Republicans on the right voted no, as did I believe, up to 90 Democrats, most of whom were from the left wing of the party. And on the day the U.S. government refused, through the vote in the House, to intervene in the markets, the U.S. stock market lost something like 8% of its value; other stock markets around the world lost 10% of its value and there was real panic, which is why they finally ended up coercing members of both political parties to change their vote to yes and to start infusing huge amounts of money into that system.

It did end up saving Wall Street. But the funds that were set aside to help homeowners and working-class people and middle-class people were basically ignored. Huge numbers of them were evicted from their homes and lost their homes in foreclosure and people to this very day are drowning in debt, generational debt, because of that financial crisis. That is absolutely the context for this debate. Namely, is this a repeat of the 2008 financial crisis? Not necessarily yet to the extent that it's of that magnitude, but that the political dynamic is the same, namely all of these libertarian “keep the government out of our lives” anti-socialist tech billionaires in Silicon Valley – who hate socialism, who hate the idea that the government steps in and helps people who are poor – “Those poor people should be self-sufficient”; “They don't need government help.” The minute their bank and their money are at risk, they start pounding the table. All to be saved. And then, the government comes in and saves them.

Let me just show you a couple of videos that set the stage for what this debate is and then we're going to go talk to Matt Stoller and see what he thinks and question him on his views.

First, let me show you the Democratic Congressman, Ro Khanna, whose views on this question are significant for two reasons: one is he absolutely holds himself out as a progressive; he ran on the view that the main problem of the United States is that there's economic inequality – the government far too often acts in favor of the rich and ignores the middle class and the working class and the poor. But he also happens to be the congressman from Silicon Valley. He represents Silicon Valley. And as you can imagine, in order to win that seat, you need the financial support and political support of the very same Silicon Valley tycoons who spent the weekend demanding a bailout for their bank. So, he went on “Face the Nation” on Sunday when he was still in doubt about whether or not the government would act. They had just interviewed Janet Yellen, who gave very mixed signals about whether she intended to do so and this is what Ro Khanna said:

(Video: March 12, 2023)

“Face the Nation”: I wonder what you make of the Treasury secretary's remarks. I know you've been in contact with the White House, with Treasury and with FDIC.

Rep. Ro Khanna: I have great respect for Secretary Yellen, but I think we need to have more clarity and greater strength in what the Treasury is saying. First, the principle needs to be that all depositors will be protected and have full access to their accounts Monday morning.

“Face the Nation”: Depositors, meaning those with accounts bigger than $250,000, which is the cutoff for insurance right.

Rep. Ro Khanna: Yes, all of them. There's precedent for this. Chair Powell when he was at Treasury, in 1991, the Bank of New England collapsed. And Chair Powell said the Treasury, coordinated with FDIC and with the Fed, and they insured every depositor. And why did they do it? They didn't want a regional run on the banks. Here's what I'm hearing from people in my constituency. They are getting nodes to pull out of regional banks, and all of this will be consolidated in the top four banks. We don't want that as a nation, especially if you're a progressive. The other thing is the payroll companies that are involved. Some of them have 400,000 folks. They're not going to be able to meet payroll if they don't have access to direct deposit.

That is the argument being made. I mean, it's amazing. I think, you know, one of the things I've noticed, as I get older, I'm not yet old, but I'm just saying as I'm getting older, is that I think one of the reasons why history repeats itself so often is because people who are young didn't live through the history and, therefore, don't know about it and other people forget it.

It's amazing how identical that sounds to the arguments made to bail out Wall Street. It was like nobody wants to help the rich. That's not what this is about. The problem is if we let AIG go under if we let other Wall Street firms go under the way we are, Lehman Brothers go under, the middle class, are going to lose their 401k, they're going to lose their retirement accounts and everybody is going to suffer.

So, yes, we're going to help the rich but work for progressives. Obama was very much in on that and he said we're not doing it to help the rich. That's just an unfortunate, incidental byproduct. The people who funded my campaigns are, of course, going to get what they want. But that's not why we're doing it. We're doing it to prevent further panic, and further runs on the bank, which would prevent people from having their retirement accounts protected or even having their jobs. Everybody would lose their jobs or there would be no money to pay them etc.

So, just because it resonates with the arguments made in the 2008 financial crisis doesn't mean it's invalid. I'm just putting in place all bear to note for a minute that if you find that persuasive, that was very similar to the arguments made in the 2008 financial crisis.

In 2018, there was a rollback of bank regulations that a lot of people, beginning where people like Senator Elizabeth Warren in today's New York Times and I'm sure Matt will be on board with their view as well. I saw AOC making this view. Lots of Democrats make this view that part of what Dodd-Frank was designed to do was to make sure that banks got a lot more regulatory scrutiny than they had previously received prior to the 2008 financial crisis. And it was a very complex regulatory scheme that was put into place. And what midsize banks like Silicon Valley Bank began to do was to make the argument through lobbyists, through paid lobbyists, that, look, these regulations are too onerous for us. They make sense for Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan and Bank of America, the kind of big four banking institutions. They can sustain this level of regulatory scrutiny. They need it, but we're not anywhere remotely in the same level of danger in terms of the risks that we're taking and especially the impact that would be caused if we do fail. And they wanted the size of the bank that is subject to this added regulatory scrutiny of Dodd-Frank to be increased from $50 billion, which is where Dodd-Frank put it to $250 billion. In other words, any institution with a total amount of deposits or assets under $250 billion would no longer be subject to this heightened scrutiny and that included Silicon Valley Bank, which was one of the banks whose CEO aggressively and actively lobbied. It wasn't like they were just a beneficiary, incidentally. They actually lobbied to change this regulation and to make it laxer, they were able to put together a majority in the first and then in the Trump administration, in 2018, most Republicans joined with a good chunk of Democrats to create a majority in favor of making those changes so that banks like Silicon Valley Bank got much less regulatory scrutiny. And here is President Trump upon signing that legislation explaining his argument for doing so.

(Video. May 24, 2018)

Pres. D. Trump: The legislation I'm signing today rolls back the crippling Dodd-Frank regulations that are crushing community banks and credit unions nationwide. They were in such trouble. One size fits all. Those rules just don't work. And community banks and credit unions should be regulated the same way and you have to really look at this. They should be regulated the same way with a proviso for safety as in the past when they were vibrant and strong. But they shouldn't be regulated the same way as the large, complex financial institutions. And that's what happened. And they were being put out of business one by one and they weren't lending. Since its passage in 2010, Dodd-Frank has dealt a huge blow to community banking. As a candidate, I pledged that we would rescue these community banks from Dodd-Frank, the disaster of Dodd-Frank. And now we are keeping that commitment and all of the people with me are keeping it. That commitment.

So, when I first begin hearing that this is all Trump's fault, that it was due to the 2018 changes to the banking regulation scheme, I was very skeptical because of the obsession, the addiction on the part of the media to blame everything on Trump. And one does have to note that President Biden is the current president. He has been the president for more than two years now, for the first two years of his presidency up until about two months ago his party, the Democratic Party, controlled both houses of Congress. There was never a time during President Trump's presidency when the Republican Party controlled both houses of Congress. Nancy Pelosi and the Democrats controlled the House during this time and yet somehow everything that happened under the Trump presidency gets blamed on Trump, whereas nothing that happened under the Biden administration gets blamed on President Biden. But with that caveat, it does seem clear, having looked at this a lot more, and beginning with that skepticism that you can draw at least something, if not a very clear and direct one between the rollback of this regulation that the Silicon Valley banks demanded, among other banks, and the fact that this bank was allowed to get very rickety, leading to a bank run, although there are still a lot of questions about.

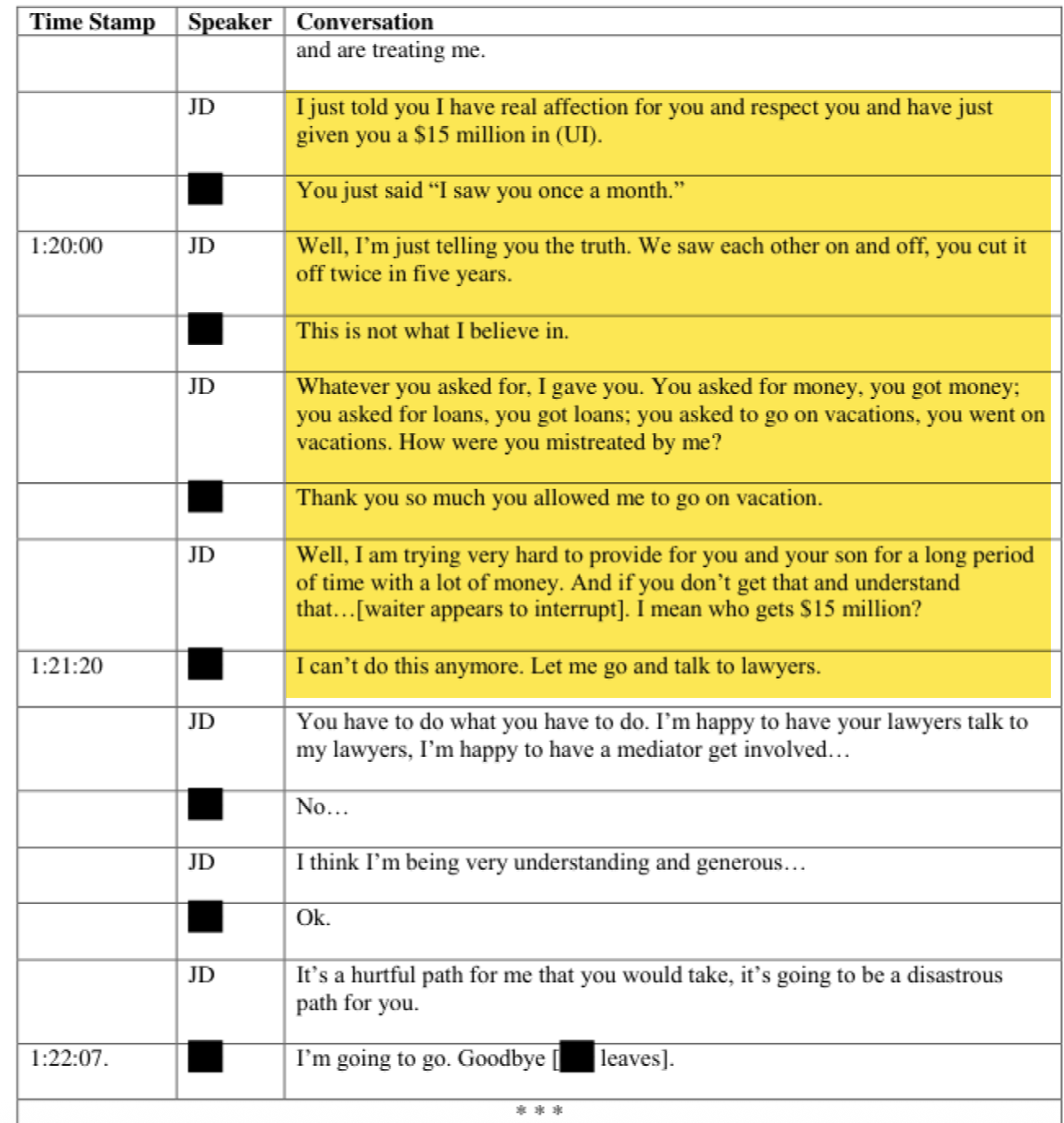

There you see the Senate roll call vote on the screen. It was 67 to 31. As most of you know, the Senate has been very evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans, very 50-50. So you only get a 67 to 31 vote if it's a very bipartisan bill. And that's exactly what happened here. So when you're trying to pick villains or whatever, that's certainly a critical question, as is the question of whether or not this added regulation would have really prevented this from happening. There are a lot of people who believe that what really happened was that the bank was nowhere near as fundamentally unstable as was suggested, that instead, because of an in-artfully worded press release and an attempt to sell off some of these assets to fix their balance sheet, a lot of people in Silicon Valley who follow these things very closely to talk to one another all the time talked themselves into a kind of panic that led to all of them trying to pull out their massive wealth from this bank that caused the bank run to happen, and that the failure of these other banks is not a reflection of systemic problems or even any sort of similar problems, that it was just contagion, that once you see one bank failing and you have your money in a regional bank, you start thinking, “Wow, I want to take my money out of my community bank, a regional bank, and put it in a much safer place like Bank of America or Wells Fargo”. And if that's the case, it's questionable whether or not added regulatory scrutiny would have solved the problem, because maybe there were really problems in this bank that should have caused it to collapse in the first place. I consider that to be one of the unanswered questions that we have to explore. But whatever else is true, the U.S. government has very quickly, very, very quickly responded to the calls of the richest people in our country, as they so often do. And the question is are they acting cautiously and wisely for the good of all of us, rather than acting corruptly to serve the needs of the people who fund both political parties?

The interview: Matt Stoller

So, to help us answer that question for our interview segment tonight, I'm going to speak to one of the most knowledgeable scholars in the country on Big Tech, on Silicon Valley. We've had him on the show many times before. He spent a lot of years working on the political capture of Washington and Congress by big in interest. He's the author of “Goliath: The 100-Year War between Monopoly Power and Democracy”. He's also the director of research at the American Economic Liberties Project. He is Matt Stoller, and we're really delighted to speak to him.

M. Stoller: Hey, thanks for having me.

G. Greenwald: Okay, So first of all, that was not yet your time to say thanks for having me. I need to first welcome you to the show. Say hello, Matt. Good evening. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me. And now you can go ahead and say that.

M. Stoller: Hey, thanks for having me. Yeah.

G. Greenwald: I'm happy to have you. You know, you're a veteran in the show. I expect you to know the timing a little bit better.

But let's get into the substance of the matter. I can scold you for that later. I want to start at the most basic level for people who do not follow these issues obsessively, who are trying to grapple with them and think about their kind of from the first principle, and that includes myself. So, let's just begin with the most basic way of thinking about this which is what is the best way to think about the relationship between a depositor of a bank and the bank itself. Is the person who's depositing money, nothing more than a creditor whose investment the government has decided partially to insure up to $250,000? Or is that kind of an archaic way of thinking about it and there's a different relationship now between bankers and depositors?

M. Stoller: No, technically that's exactly accurate. And, you know, it's not just that the government decided in the 1930s we had bank runs all the time that was similar to Silicon Valley Bank, except it was everywhere and people would lose everything. And so, the government and banks kind of cut a deal, right? And democratically. And what they said is we are going to make insurance so that if a bank goes under your deposits up to a certain level – the ordinary people don't have more than $250,000 in an account – you're going to be insured, so you're fine. You don't need to worry about your bank unless you are really rich or your business has a lot of cash.

Then the banks get really cheap funding, so they get to borrow really low cost and then they lend at a higher cost and they essentially get free profit. But in return for essentially being able to use the government's full faith and credit – the government credit card – they have to accept supervision and regulation so that they're not gambling too much with the government's money. And that was kind of the deal and it prevented bank runs, which are horrible, pretty much until – I mean, you could go the seventies, eighties, nineties in various ways – but you know essentially they still prevent bank runs and your bank account up to $250,000 is still safe.

There's also a variety of other institutions like the Federal Reserve and the Federal Home Loan Bank program which create what is known as the safety net for the banking system. So really, the banking system is a public system. I mean, people think about banks as private institutions and bankers as businesspeople, but really they kind of have a public obligation as well, because they draw so much support from the safety net. But there are good reasons to have a safety net here.

Now, I have a lot of rage over the situation, but I'm just trying to give you an analysis of why we have FDIC insurance, why your money is probably safe in the bank account unless you have more than 250,000 and setting up for some context to discuss not just Silicon Valley Bank, but the Fed and FDIC also quietly resolved a different bank signature bank in New York, which is only $107 billion of assets and that's a crypto bank and they kind of snuck that one in as well.

G. Greenwald: That's Barney Frank's bank, right? the bank where he's a director…

M. Stoller: That's right.

G. Greenwald: So, I'm going to absolutely, deliberately, provoke your rage as I love to do. It's actually not that hard. But before we get to that, I just want to spend a couple of more minutes on kind of the foundational understanding. So, we have the culture of the basics to work with.

If this model is correct that you just described – or that I describe and you kind of accept it and then added to – which is, so, I'm someone who grows and I have a lot of money, I want to put my money in a bank and maybe I have a lot of money, not because I'm rich, but because I have a startup company that people just invested in. Someone gave me $50 million because I need startup cash for my company to develop a new technology – to pay the people who are going to develop it for me. I need a place to stick my money. I stick it in Silicon Valley Bank because it's a 40-year institution, it's well-regarded, and it's something that seems profitable. And then let's assume that the people who run the bank do all kinds of bad and reckless things. They lobby the government for less regulatory scrutiny. They make really terrible decisions. They make bad bets. I think everybody understands that those people who make bad bets and who are reckless should lose whatever gains they would have had. And should basically lose everything, especially if the government has to come in and save them.

Why, though – the depositors who didn't do anything wrong or who didn't bet wrong, they're just putting their money in a bank that has a well-regarded reputation – why should they lose their money? About $250,000. Just because the executives of this bank acted irresponsibly?

M. Stoller: Well, there are two reasons. First of all, it's uninsured. It's not a secret that the FDIC limit is $250,000. It's plastered everywhere. So, if you're a treasurer of a corporation or a municipality, you know the score and you're choosing to ignore the rules. And that's just capitalism: sometimes you take a loss if you make a bad decision. And the other reason is, first of all, let's just be clear, uninsured depositors are not going to be wiped out. In fact, they'll probably get 80 to 100 cents on the dollar […]

G. Greenwald: Because the government intervened. But had the government not intervened, they would have been wiped out.

M. Stoller: No, no, no. The government comes in and sells off the assets of the bank and then pays back the uninsured depositors with whatever they get for that. And Silicon Valley Bank, though, it lost money on bonds – those bonds are still high quality, they just dropped in value somewhat. So, what would have happened is the FDIC would have come in and taken those bonds, sold them off and then, today, people would have gotten between 30% and 60% of their uninsured deposits back. Then, over the next 2 to 6 months, they would have gotten whatever remained from the FDIC selling whatever they could for whatever they could get. And it's likely that people would have gotten 80 to 100 cents on the dollar of uninsured deposits back.

So, there was no way that people were going to be wiped out by this. What might have been some problems getting access to all of their funding immediately? They would have gotten access to some of it immediately, but not all of it. So really, like the panic here and it was panic, it was, I think, kind of silly the idea that you need to backstop so people get 100% of their deposits immediately was just regulators panicking. And that's all this was.

G. Greenwald: But their argument was, look, even if down the line we get a good amount back, in the meantime, we can't pay our payroll, our businesses are going to go out of business. They're going to lose tons of start-up in them. And the technology they would develop that would drive the future gross domestic product to the United States. That was the argument.

M. Stoller: No, no, I know. And you've been feeding it to me all day to get me angrier and angrier. So, I appreciate that.

G. Greenwald: (laughs). But what's the answer to that argument?

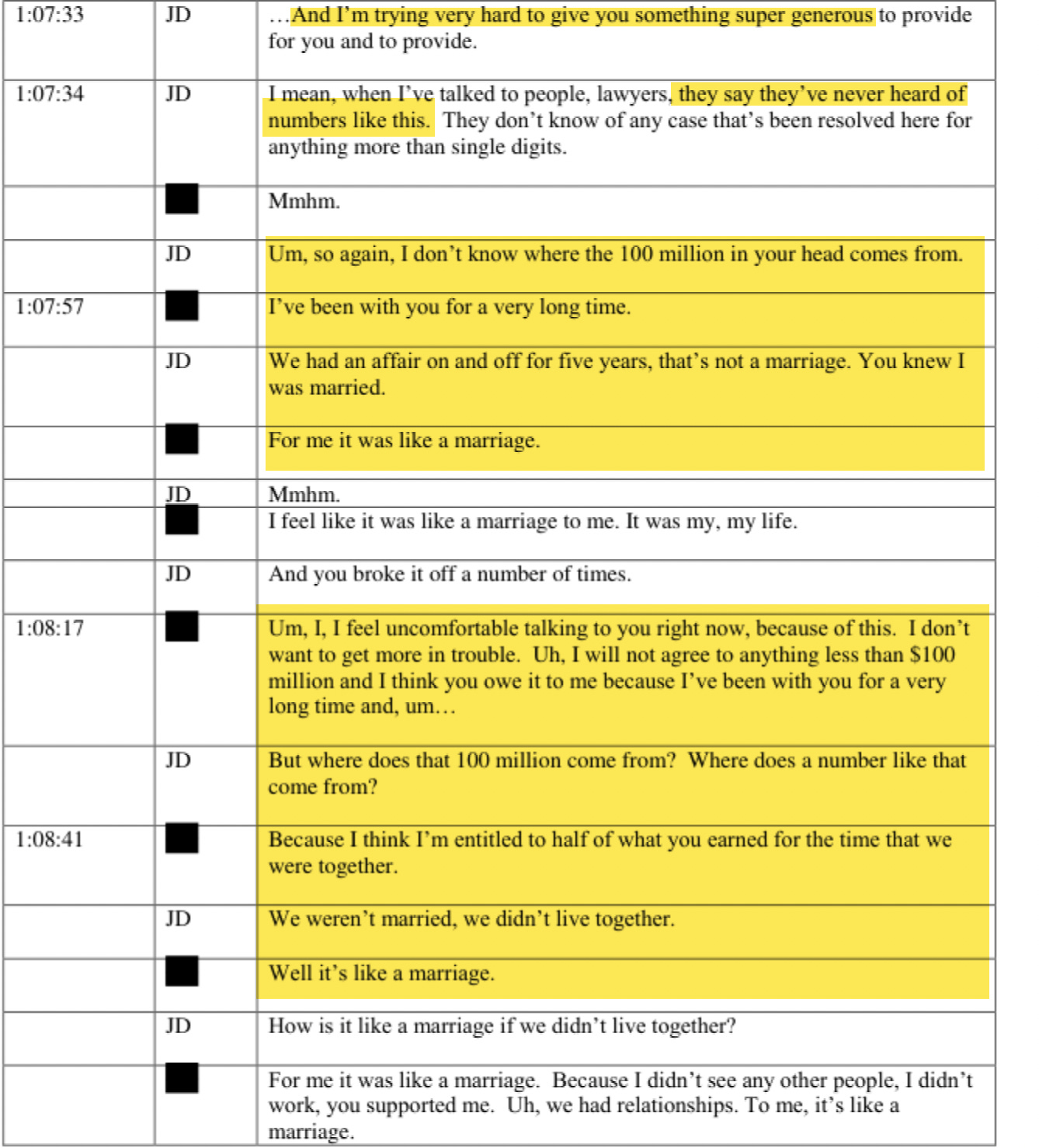

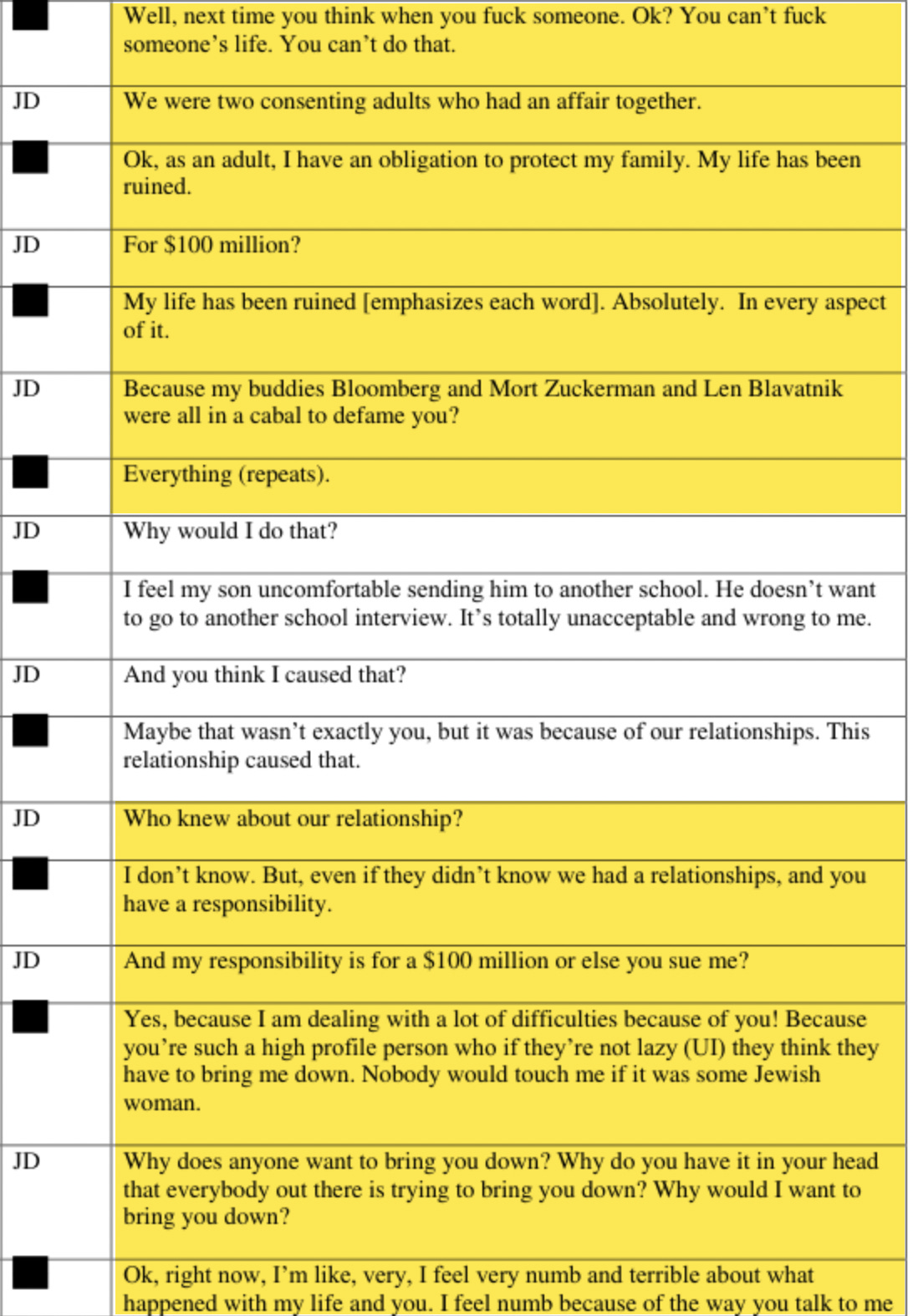

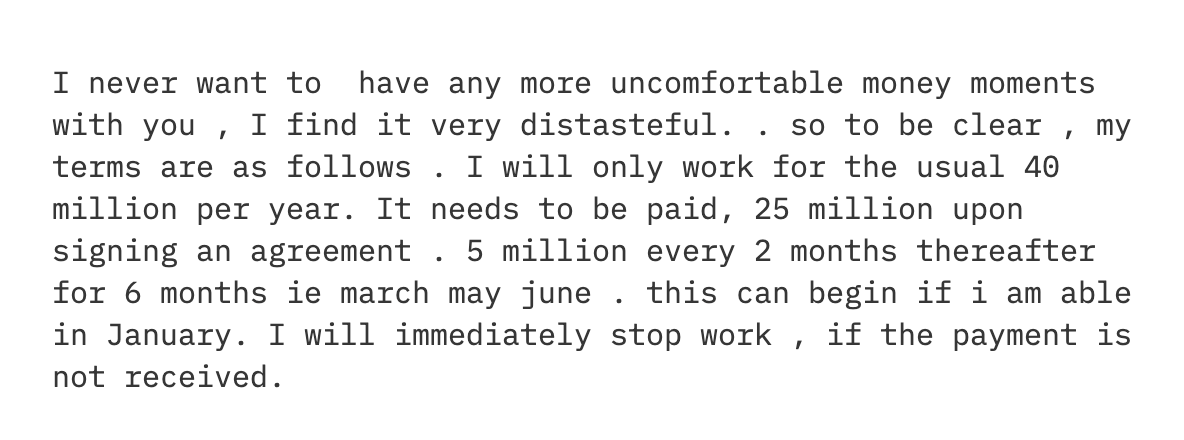

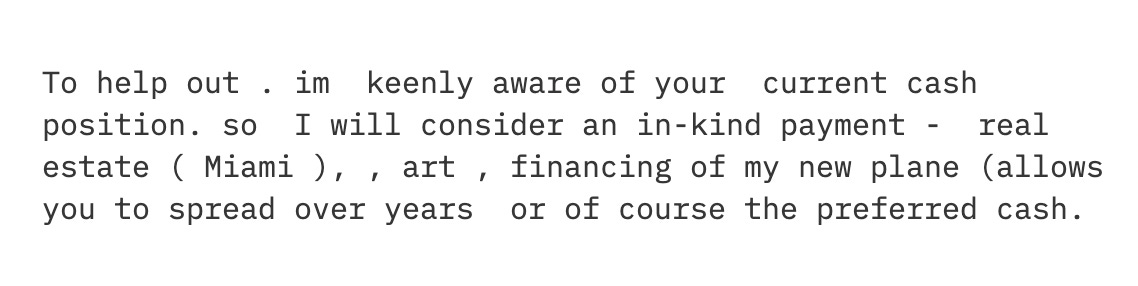

M. Stoller: Well, these are not innocent people, right? These are rich people. These are powerful people. They know there's a $250,000 limit. So why have they been violating that when in a lot of cases you have treasuries that don't do that? There are services that you can get at banks called cash sweeps, which let you chop up your $10 million into 40 different $250,000 FDIC-insured accounts. Why didn't they use that?

Well, the answer is because Silicon Valley Bank was not just an innocent bank. What they were doing is they were saying, if you leave the money from your firm or from – if you're a venture capitalist – the firms that you fund, if you leave them as uninsured deposits with us so that we can gamble with them, we will give you what's called “white collar banking services”, which is to say below cost personal lines of credit, below cost mortgages – essentially the kinds of things that politicians are criticized for because it's essentially bribery.

The Silicon Valley Bank was essentially giving stakeholders in Silicon Valley bribes to keep their money as uninsured deposits so that they could gamble with it. And that's why these guys took a risk. They were also getting much higher interest rates on their uninsured deposits – they were getting more for taking more risks. So, they should bear the costs of that. And not just that but Silicon Valley Bank was also a co-investor in a lot of these firms. So, Silicon Valley Bank had stakes in over 3000 different tech companies and as a condition of those stakes, it was saying you have to have that firm deposit its cash with us in uninsured. So, there were a lot of elements here where there was self-dealing, there was a bad regulatory system, and then there was the Silicon Valley Bank bribing the people who were in charge of other people's money. So, this is a nasty situation. These people do deserve to have a minor haircut off of their deposits. And it would be – it is – completely crazy what the administration has done – and I blame Janet Yellen for this and I blame the Federal Reserve and I blame Joe Biden and I blame Donald Trump – It is absolutely outrageous that they have made these guys whole. All this was just panic and corruption and greed. And it was totally outrageous and disgusting and I am disgusted by it.

G. Greenwald: So, let me ask you, Matt, if you talk to the people in Silicon Valley who wanted this, this is their argument. Their argument is this: look, there is nothing special about Silicon Valley Bank. The reality is there are a ton of regional banks and community banks in the United States that are suffering in large part because the Fed raised interest rates. So, I don't really get that argument since the Fed always telegraphs, and especially in this case, telegraphed it very loudly they were going to do that. But their argument is we're not any different. And if you don't back this up and if you don't protect depositors, the thing that's going to happen in the next 48 hours, which seems kind of reasonable to me as a prediction, is everyone's going to get spooked towards their money – you heard Roe O'Connor. This is his argument – in a regional bank or in a community bank. And they're all going to say, you know what, I'm getting my money out of there as quickly as I possibly can. I'm going to put it in one of the big four and every regional bank in the United States is going to collapse. And the only thing that's going to prevent that is if Janet Yellen comes in and says, don't worry, we're here to ensure every penny of your deposits.

Why isn't that a valid argument?

M. Stoller: It's not a valid argument because we have a system that's set up to address that problem. One question that we have to ask is why didn't Silicon Valley Bank have the cash to give to depositors. Well, one reason is that they weren't keeping enough cash on hand because of the deregulatory choices and bad regulatory decisions by the San Francisco Federal Reserve.

Another reason is that they just didn't have the assets they needed, right? The Federal Reserve is a bank of banks, and if you need a bunch of cash, you can just go to the Federal Reserve and say, I have a bunch of Treasury bonds or loans or mortgage-backed securities or whatever I need to borrow from you. I'll give you these as collateral. You give me the cash and I'll give it to my depositors, when things blow over, they'll come back and redeposited the money. And we have a system that's set up to deal with large demands for cash.

The reason Silicon Valley Bank couldn't take advantage of that system is they didn't have the necessary collateral because they were insolvent. Most of these regional banks are not insolvent. And also, most of these regional banks are funded by insured deposits, so, people with less than $250,000 who have no reason to move their money. Silicon Valley Bank was funded 97% with uninsured deposits. Signature Bank, which is the other one – that was Barney Frank's bank and Ivanka Trump was on the board of that one before Barney Frank was – that was 90% uninsured deposits. The next most likely bank to fail, called First Republic, which has about 67% uninsured deposits. And from there, it goes way down. So, we're really not dealing with a system that is – I mean, there's some trouble because the Fed keeps raising rates – but, as you put it, the Fed has telegraphed this. These guys just chose not to hedge because it would – actually their own employees were telling them, you got to hedge. This is really dangerous as interest rates rise. And the bankers were like, yeah, we don't want to, we won't make as much money. They were making these choices, they were remitting some of the extra profits to the uninsured depositors in the form of – what I've said before, these quasi-bribes. And they're pretty unusual bank. Most regional banks are not like this. So, you might have an initial panic. You might take down one or two or three other banks, but it'll blow over and then you will have re-imposed market discipline. Instead, what we did is we said everyone's going to be made whole; Silicon Valley bank depositors who took these massive risks, they're going to be made whole; all banks except for Silicon Valley Bank and Signature, their funding costs are going to go down and we're going to hand them all the full faith and credit of the United States that they can go off and gamble with. And there we go. Problem solved. Like that's what we did. Instead, this is just like a panic. And instead of dealing with banking panics the way that we should, which is to just use sort of like take out the bad banks that are insolvent, you let them go insolvent and everybody else –you lend them to tide over the panic. They freaked out and did a giant bank bailout and I think the reason this is different from 2008 is there are losses [...]

G. Greenwald: Oh, hold on. I'll probably get there before we get there. I just want to address my audience for one second because people are telling me in my ear that they’re treating you and cheering for you like you're some kind of Huey Long populist and wondering why I've suddenly transformed into Tim Geithner performing Propagandistic Services on behalf of Silicon Valley oligarchs. So, I just want to be very clear that the format of the show, on purpose, and I thought I said this at the beginning, was I was going to have Matt on – whom I know for certain, and somebody very vigorously opposed, in fact, angrily opposed to what the Treasury Department is doing – and I'm presenting him the arguments in favor of this bailout, not because I share those arguments or believe in those arguments, but because I think the best way to have this show be the most informative, is to allow you to hear Matt responding to the arguments of the people defending this, which are not necessarily my arguments just because they're coming out of my mouth.

So, let me ask you, Matt, now that I've taken off my Tim Geithner costume – although I'm going to put it back on, the proviso that I'm wearing it on purpose, what about 2008? Because that obviously is the thing that I think a lot of people are thinking about. I've seen lots of debates. Is this a 2008-style bailout? Is this something different? Obviously, the magnitude is a completely different universe but, in terms of the mentality, it seems like what this is, is the government stepping in and defending and protecting the assets of rich people as they did in 2008, because that's whom they serve, because that's who funds them. Is that one of the right ways to think about what's happening here?

M. Stoller: Yeah, there's a couple of differences between 2018 and then some similarities. I feel like this is like a high school essay. There are similarities and differences. So, the difference is that, in 2008, people were freaking out because the banks had invested in a bunch of crappy mortgages and nobody knew what anything was worth. So it wasn't that there were losses, it was that nobody knew how big the losses were or whether anybody was solvent. So, it was a panic, but it was a panic that was like – it was a very rational reason to panic because you didn't actually know what anything was worth and you didn't know if any institution was worth anything. And neither did any regulators. And it took a while to sort that out.

In this situation, there are losses, but we know what those losses are. It's pretty open and it's not like we're going to be that surprised. The Fed has been telegraphing that it's raising rates. Everybody knew that Silicon Valley Bank had losses on the books. And then, there’s these other regional banks. We know what they've lost. So, this is not that big a deal. There is some panic in the markets, it's a serious situation but it's not a crisis situation.

But in terms of the similarities, I think what you see is exactly the same attitude of 2008, in 2023. I mean, one of the differences is, in this case, the stockholders and the bondholders are not getting bailed out, but the uninsured depositors are. So, in that sense, it's, I guess, a little bit better than 2008, because, in 2008, they bailed out the stockholders and the bondholders and then the executives got bonuses. This time, at least they have to give the bonuses before the bailout. But yeah, the attitude is similar. And that is why I'm angry because we've seen this movie before. And in this case, they didn't need to do it. In 2008, I think that they needed to do something, there needed to be capital injections – the way they did it was problematic – but in this case, they didn't actually need to do it. And that was pretty obvious.

G. Greenwald: Okay, so that's one point. The next thing I want to ask you about, is, as I said, there does seem to be an addiction on the part of the political class to blame anything and everything that happens instantly on Donald Trump and only on him. It absolutely is true that there were rollbacks of Dodd-Frank, in 2018. We played the bill signing where Trump announced the rationale that led him to sign this. It definitely ended up excluding Silicon Valley Bank because, by raising the threshold to $250 billion, from $50 billion, they would have been subject to this scrutiny. And with this change, they ended up excluded.

What I'm wondering is this: what it seemed to me like in real time – and I've read the accounts of some of these people who are extremely wealthy individuals who tried to take their money out of Silicon Valley Bank on Friday to find that they couldn't do so – but it seemed to me what happened was panic – as you said, in 2008, it was kind of rational, you looked at the markets and there is reason to think these institutions might be insolvent or at least have no idea whether or not they were – in the case of Silicon Valley Bank, they definitely had losses on their balance sheet, but it doesn't seem to me that they had the kind of losses that warranted a panic or a bank run.

What instead happened is that you have this very incestuous group in Silicon Valley that started whispering to each other “you better take your money out”, “you better take your money out”. That spread very rapidly. It proliferated and everybody took their money out. Of course, Silicon Valley Bank didn't have the liquidity to cover that. If that's true, or some version of that is true, what I'm wondering is let's assume that there hadn't been this rollback of the Dodd-Frank regulations in 2018, that you had the regulators subjecting Silicon Valley Bank to the same stress test that it would have gotten before the rollback in 2018. Is it really that clear that the federal regulators would have blown the whistle on Silicon Valley Bank said its balance sheet is way too risky or way too far away from what is safe or would they have looked at it and said, you probably should do what they ended up doing, selling off some mortgage-backed securities, doing some stuff that you talked about with the Fed in order to bring in more liquidity, unload some longer-term assets – which is what they did, that, in turn, further fueled the fear. I'm just wondering, is it really that clear that if regulators had taken a look at it under the hood, they would have freaked out the way that these depositors did?

M. Stoller: I don't know that it's clear. Yeah, sure, they engineered a bank run, but I don't put it on the depositors – they freaked out for a rational reason which is that the bank might be insolvent and probably what they did was smart. If you think that the bank is not going to have your money and your money's not insured, you should pull it out and get it out before everybody else. That's what causes a bank run.

So, it was sitting there like it was kindling waiting to go up in flames. And, you know, it just so happened that it was a group of people, I don't know, slack or whatever, or signal, that lit the flames, but that was going to go. I don't know that you can definitively claim that bank or bank regulators would have forced Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank to have more liquidity on hand and to not have made so many egregious bets. I just don't think you could say that definitively. But I do think you can say that it's more likely they would have definitively. However, the other point here is I think there's a sort of 1, 2 problem here because – I worked on Dodd-Frank – and so, first of all, you're welcome. We fixed everything as everybody […]

G. Greenwald: Including Barney Frank’s bank.

M. Stoller: The dirty secret of Barney Frank is he didn't actually know anything about banking, which was, like, kind of hilarious. But […]

G. Greenwald: But he had a lot of friends in banking.

M. Stoller: Right. Well, we could go into a whole thing on Barney Frank.

But in 2009 and 2010, what we effectively did is we institutionalize too-big-to-fail banks. So, the four or five big banks that are too big to fail, we said we're going to make it too big to fail, and maybe we're going to regulate it a little bit more aggressively. And then there's them and then there's everybody else.

Then, you move forward and the regional banks, who are very large but not as large as the big banks, they say, well, we want to be able to gamble a little bit more aggressively and then they convince the Republicans to go along. The Republicans never like bank regulators or banks – there was like a really interesting rethinking of significant parts of the Republican orthodoxy agenda like trade and antitrust. But one thing that the rethinking didn't get to, the realignment didn't get to, was banking rules, although I will note that on March 3, a bunch of Senate Republicans sent a letter to the Federal Reserve being like, you better not regulate more aggressively. We passed a bill in 2018 to make sure you don't. And J.D. Vance was not on that letter. There is some reason to think that some of the younger Republicans are changing their thinking. But it is certainly true that, in terms of bank regulation, this is still George W Bush's party, right? It didn't change.

But I think that this was kind of like a twofer. Like we created the too-big-to-fail problem in the 1990s and 2000 and we institutionalized it with Dodd-Frank and then, we allowed these regional banks to go crazy, in 2018, and created this situation, in 2023, when these regional banks had gambled with other people's money and kind of had this collusive arrangement with these uninsured depositors.

There was an argument, ‘oh, everybody's going to just go to move their money to JPMorgan because it's essentially a government bank’. It's a somewhat reasonable argument. I think it's overstated. I just don't think there was panic in most places in this country – this was a very online sort of echo chamber. But it's not an unreasonable argument. I think what we have to do now is look at the banking system and say, banks unless you're really small – In which case we can just kick you around because you have no political power – unless you're really small, you are effectively a government bank. And we need to just treat you like you are a government employee. You're a GS-15. You don't get to gamble with taxpayer money and pay yourself large amounts of money in bonuses or share buybacks or whatever. That's kind of where we are and if we want to move away from what is effectively a socialized system, which I think we should, then we should do that but right now, we are at a kind of socialized system, and it is the Democrats under Obama, it was the Republicans under Trump. And then, it's also the Democrats under Biden and Yellen. Although I'll say this, some of the things that Biden was trying to do, like he was trying to put this bank regular name, Saule Omarova, who opposed the 2018 bank deregulation, and she got blocked by essentially the same coalition of people who passed the 2018 bills, which is all the Republicans and then some Democrats. So, it's not totally clear here but what is 100% clear is that, broadly speaking, the political class, entirely in the Republican Party and then some of the Democrats and certainly at Treasury and the Federal Reserve are wholly in favor of bank bailouts for the wealthy and the powerful. You can argue about when they're necessary and when they're not. There were certainly some innocent people who were going to get hurt here but broadly speaking, what just happened was very bad and is an indictment of our regulators and our political class.

G. Greenwald: In terms of the last question, I mean, I think if you're listening to that and you're Republican, first of all, there's probably a lot of Republicans who want the party to move more in the direction of the J. D. Vance of the world and get away from the Mitch McConnell and the kind of where we're serving the lobbyist class, right? But, nonetheless, even going back to 2008 – with Hank Paulson and George Bush's bailout that both McCain and Obama and Canada had signed on to – the reason it failed at first was that a lot of Republicans voted no. Not a good number, Democrats and Republicans. And their attitude was exactly that, which is like, ‘No, we don't want the banking system nationalized’. We don't want it socialized; we don't want it federalized. But what we also don't want is, when it does fail, you look to the government and we come in and save you. Too bad, you're not getting our help.

Is that a viable alternative to saying to the banks you're now under federal control? Or will it always be the case that at the end of the day the government's going to have to come in and save the banks because if they don't, the harm is going to be too widespread?

M. Stoller: Banking is always a public business, right? I mean, that's just that the bankers like to pretend that banking is private and bankers are running private businesses. But the reality is that when you get a bank charter, it's a government license and you get access to a whole social safety net. That is the thousand Federal Home Loan Banks, the FDIC, and all bankers take advantage of it. They want to take advantage of it. And they just bristle at the oversighted regulations because they can't gamble as much. So, it is a public system. But within that context, they have to do or they should do risk management.

And the question is, how do they get penalized when they don't do adequate risk management? And the way we used to penalize them is their shareholders, their bondholders, uninsured depositors and bankers themselves got penalized. And today, it seems like where we've moved to is that if you're rich and powerful, you get profits, but no losses. Those are just fundamentally different systems, even though both of them are public systems. This last one, I think the one where we've socialized all the losses, I think, it's far more of a step towards kind of a nationalized system. It's just a very terrible nationalized system versus the kind of earlier, hybrid one where they did take losses sometimes. So, I think what we need to just acknowledge is that this is a public-private system and that we have to impose some form of market discipline, but also allow for stability. So, allow for insured deposits, but make sure that if, you're not insured, that you have to do risk management. And then, I would also say that a lot of business people just want a place to put their money that is safe. That's all they want. And why should we force them to be effective what is a government bank like J. P. Morgan or something like that? They should just be able to get an account at the Federal Reserve, right? If they're going to have a government bank, it's either going to have an implicit backstop or it's just going to be explicit. And why not just like it's a public service? So, let's just have it go through the government itself versus what we have now, which is, you know, we're having government banks. It's just we're paying the people, running them way too much and they get to gamble with our money. So, I don't know if I answered your questions, like there are inherently public characteristics of a banking system, but it doesn't have to be sort of a totally nationalizing of the downside, which is what we've been doing over the last 10 or 15 years or so.

G. Greenwald: But in this case, just to conclude, if you were the Treasury secretary or if you're the president, what would have happened is you would have let Silicon Valley Bank be on its own, have the FDIC come in and take it over, sell off its assets, give the depositors as much as possible over the amount of time and hope that you're right, that it would have only been a couple of banks that would have gone down in the resulting panic but in the system in large, the banking system is fundamentally sound. That's your view.

M. Stoller: Yeah. And look, if there had been like a broader crisis and, all of a sudden, there was this massive solvency problem – like then you come in and you go to Congress and you say there is going to be a serious banking crisis and we need capital injections and we're going to attach really serious strings to that – but you don't just start with the 16th largest bank in the country, that's just $200 billion of assets and a bunch of venture capitalists. And Larry Summers starts to say, “oh, you have to make my buddies whole”. You don't just respond to that. You have to have real evidence that there is a systemic crisis. Otherwise, it's illegal, right? I mean, the logic is clear. So, that's just where you have to have some ability to stand up to panic. And that's like what these guys don't have, they're just like, you would say boo and they they're like, Oh, where do I write the check?

G. Greenwald: So, I said in my introduction, that one of the things you study is the capture of government by finance. Is it your view and I know it's hard sometimes to kind of talk about people as a monolith and to know people's motives. But Janet Yellen's been around for a long time, as you can see. If you listen to her, watch her, she obviously is aware of both sides of this argument.

Is it your view that she wasn't willing to let this panic spread out of fear that it was more systemic and she thought it would be better to capture it, just stop it when it first started? Or do you have the more cynical view that these rich people have tons of power inside the office of these decision-makers – which, of course, they do – and that's why they ended up getting their way?

M. Stoller: Well, I don't think those two stories are mutually exclusive. I don't think that any of these actors were acting in bad faith. It would be easier if they were, right? If they were just scheming corruption and they were just like, “aha, I'm going to bail out my rich friends”. It's much worse than that. It's like they actually believe they're their rich friends when they say everything is going to collapse. That's what actually is going on here. They were like, “oh, my gosh, if Larry Summers says that everything's going to collapse, I better act”, right? They believe, they get spooked easily, and the people that don't are the people that get blocked from being put into office. They bring up Saule Omarova. She would not have stood for this if the Senate had confirmed her at the Office of Comptroller of the Currency, she would have been like, no, this is bullshit. And so, I think that part of the problem here is that the people that you – Janet Yellen has been terrible for a really long time. And, you know, she got bipartisan confirmation and the rest of it ends like you can go back to the the Trump administration and you'd find the same thing. It's the people who are actually really courageous and willing to stand up to the financial power that have a tough time getting confirmed. And so that's kind of, you know, they intentionally select people who are weak, right?, for these positions.

G. Greenwald: Yeah. All right, Matt. Well, unless there's anything else you feel I need to get off your chest and, you know, you'll always have a welcome spot here to do it. It's like a massage therapy spot. I want to thank you so much for taking the time. It was super enlightening. Gave me a lot of arms to talk to David Sachs tomorrow when I do, about his side of the story. So, if you don't have anything else, let me say goodnight and thank you again for taking the time.

M. Stoller: All right. Thanks so much, Tim Geithner.

G. Greenwald: All right. (laughs).

Monologue

So last night was the Academy Awards, if you're like most people these days, actually, in America, you did not watch it, even though it used to be one of the events that brought all of Americans together. Increasingly, the ratings are collapsing for all sorts of reasons that we can go into. At some other point, I bet the number of people who could actually name the film that won best film in the 2022 Oscar ceremony is under 4% or 5%. I actually read it this morning and I've already forgotten it. I was about to tell you I'm proud of myself for having done that research, and yet it's already out of my brain. I didn't see that film. I don't think I saw any of the nominees. That's increasingly true for a lot of people.

So clearly the Oscars have lost a lot of cultural impacts and I nonetheless want to talk about it for a very specific reason. And I'm going to just spend a little bit of time on it because that's all I really deserve. And I'm much less interested in the issue of the Oscars itself than the broader issue that I think it highlights. So just to give you the setup and the issue that I want to talk about is the category of best documentary. And I do have a personal stake in this somewhat, which is that my friend Laura Poitras – who directed Citizenfour, which was the film, a documentary about the work that I did with Edward Snowden in Hong Kong that won the best Documentary Oscar in 2015, was nominated for a film about the opioid crisis that I actually expected was going to win. I haven't seen any of these films other than hers, including the film talk about, so I want to put that card on the table as well. That film that Laura did, which would have been her second Oscar win, ended up not winning. I honestly don't care. Laura has won every award there is in this world, basically, and she didn't need a second Oscar.

Anyway, the film that did win is a film called Navalny, which is a documentary about the Russian dissident who is currently imprisoned because he is an opponent of the government of Vladimir Putin and you can imagine how popular he is, even though he has said things his whole life that should make him completely anathema to liberal America. He has said some of the most vicious and bigoted denunciations of the Muslims of the world. He was taken off the list of a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty because of some of his most recent statements that he refused to recant. But that doesn't matter. Just like liberals are eager to arm actual neo-Nazi militias in Ukraine. All that it takes these days to be a hero is to either be opposed to Donald Trump or be opposed to Vladimir Putin, and everything else is completely irrelevant. And that's the reason they gave this Oscar for this film about Navalny. And I just want to show you what happened in the two and a half minutes that resulted in them winning (Video).

Presenter: And the Oscar goes to… Navalny. […]Diane Becker, Melanie Miller, Shane Boris…

OFF: Director Daniel Roher and his team filmed Alexei Navalny while he was in hiding from the Russian government at a remote location in Germany.

Daniel Roher: Thank you to the Academy. We are humbled to be in the company of such an extraordinary crop of documentary filmmakers. These films redefine what it is to make a documentary. To everyone who helped make our film, you know who you are, your bravery and courage made this film possible. We owe so much to our Bulgarian nerd with his laptop, Christo Grozev. Christo, you risked everything to tell this story, and it's investigative journalists like you and Maria Pevichikh that empower our work. To the Navalny family. Yulia, Dasha and Zakhar, thank you for your courage. The world is with you.

And there's one person who couldn't be with us here tonight. Alexei Navalny, the leader of the Russian opposition, remains in solitary confinement for what he calls – I want to make sure we get his words exactly right – Vladimir Putin's unjust war of aggression in Ukraine. I would like to dedicate this award to Navalny, to all political prisoners around the world. Alexei, the world has not forgotten your vital message to us all. We cannot, we must not be afraid to oppose dictators and authoritarianism wherever rears its head. I want to invite Yulia to say a few quick remarks. Yulia.

Yulia Navalnaya: Thank you, Daniel. And thank you to everybody. The everybody here. My husband is in prison just for telling the truth. My husband is in prison just for defending democracy. Alexei, I am dreaming the day when you will be free and our country will be free. Stay strong, my love. Thank you.

Okay. All incredibly moving, and emotional and obviously, I'm sure people in that room, the people who voted for this film, felt very good about themselves. They were taking a stand against Russia, against the Russian dictatorship. They all were cheering. The person who directed the film that won the Oscar said, “We need to stand up to dictatorship wherever it rears its head”.

I think one of the things that makes us so notable is that during the Cold War, the idea of whataboutism was often denounced by the U.S. government, and the way they define that was that they would always claim that any time you criticized the Soviet Union and its abridgment of basic liberties and rights, the Soviet government would try and distract attention away from that critique by saying, “well, what about your problem over there in the United States with how you treat black people? Or what about the internment of Japanese Americans?” So, they would kind of distract their own citizens’ attention away from the critiques of their human rights abuses by pointing way over to the other side of the world, the United States. And they would always say, what about this? What about that? What about this?

Now, the idea that some sort of Soviet practice that they invented is lunacy. Humans have been doing that from the time that they could speak. You say, well, you have this fault and they say, no, what about my neighbor? My neighbor has it far worse. There's a very human practice. The Soviets did not invent theirs, but that was always the framework. That was the idea was the governments do, in fact, use this tactic to distract attention away from their own abuses.

It's not just the Soviet Union that does that or the Russian government that does that, it's also the United States that does that, we're experts at it. We love to say things like we will stand up for democracy, despotism and tyranny wherever we find it. We will stand up to Navalny, to this person over here in China who's imprisoned unjustly, or this person here in Iran. And, of course, the United States has always had and still does have its own dissidents in prison and one of the leading ones, for example, is Julian Assange.

And so, it seems very strange to me, very strange, to have a room full of people cheering not just the film, but themselves, for very – it's a very empty and cowardly thing to do, to denounce the government on the other side of the world over which you have absolutely no influence. Denouncing Vladimir Putin or President Xi or the Iranian mullah is really doesn't do anything to change those governments. You have no influence there. It's not a brave thing to do. You're not in danger there. You don't live in those countries. It's always been the case that foreign countries that are enemies of one another criticize each other. That's all this is.

What makes a lot more bravery and that's a lot more consequential, is criticizing the human rights abuses of your own government. And if you don’t ever do that, if instead you're constantly focused on the human rights abuses of other governments, it actually empowers your own government to engage in the same human rights abuses because you're constantly reaffirming its narrative that it's only those bad countries over there that imprison political dissidents and political opponents. We absolutely do the same. Julian Assange is in prison, in part because he exposed the crimes of the United States government, but also because – and I think this is really the bigger part – is, in 2016, he published documents that helped Donald Trump win the election and Hillary Clinton lose the election. Because before that, many Democrats and people on the liberal left are very much in support of Julian Assange and now it's almost impossible to find anyone on the liberal left willing to stand up in defense of Julian Assange. And the only thing that changed was that he did journalism that helped defeat Hillary Clinton. That is the classic case of being a political prisoner. The Biden administration is doing everything possible to keep him in prison for as long as possible, despite never having been convicted of a crime. And it is unimaginable that these same Hollywood liberals would give an award to a dissident like Julian Assange.

Now, when I said this earlier today, people pointed out that the same Hollywood liberals who vote did, in fact, give an award, the Oscar, to the best documentary that Laura Poitras produced about my work with Edward Snowden. I went up on the Oscars stage. We collected the Oscars, but they were for Laura and for the two producers of that film. But I think especially in the wake of Donald Trump, everything changed in terms of how American liberals think. They've become much more jingoistic and they never like to believe their own government engages in the kinds of abuses that the Russian government engages in. And not only is it just a vapid and cowardly thing to do – spend so much time focused on the bad acts of a government far away from you over which you have no control or you can't change it while ignoring the abuses of your own government – it actually makes it even more difficult to do anything about the abuses of those foreign governments, because if you try, other governments will look at you like you're crazy – like, who are you to lecture us on the rights of dissidents when you imprison your own dissidents yourself? Why would we possibly listen to your lectures?

There was an incredibly powerful example of this when President Ilham Aliyev, of the above Azerbaijan, who for sure is a savage authoritarian, was confronted by a reporter from the BBC about Azerbaijan's imprisonment and other abuses towards dissidents. And you'll see how he used that argument. Listen to what he said:

(Video. Nov. 9, 2020)

President Ilham Aliyev: Why do you think the people question do not have free media and opposition?

Orla Guerin, BBC: Because this is what I'm told by independent sources in this country.

President Ilham Aliyev: Which independence sources?

Orla Guerin, BBC: Many independent sources.

President Ilham Aliyev: Tell me, which.

Orla Guerin, BBC: I certainly couldn't name sources.

President Ilham Aliyev: If you could name that means you are just inventing this story.

Orla Guerin, BBC: So, you're saying the media is not under state control?

President Ilham Aliyev: Not at all.

Orla Guerin, BBC: I mean NGOs are the subject of a crackdown. Journalists are the subject of a crackdown.

President Ilham Aliyev: Not at all.

Orla Guerin, BBC: Critics are in jail.

President Ilham Aliyev: No, no,

Orla Guerin, BBC: none of this is true?

President Ilham Aliyev: Absolutely fake. Absolutely. We have free media. We have free Internet. And the number of Internet users in Azerbaijan is more than 80%. Can you imagine the restriction of media in a country where the Internet is free, there is no censorship and 80% of Internet users? This is, again, a biased approach. This is an attempt to create a perception in Western audiences about Azerbaijan. We have opposition, we have NGOs, we have free political activity, we are free media, and we have freedom of speech. But if you raise this question, can I ask you also, how do you assess what's happened to Mr. Assange? Is it a reflection of free media in your country? Let's talk about Assange, how many years he spent in the Ecuadorian embassy and for what? And where is he now? For journalistic activity you kept that person hostage, actually killing him, morally and physically. You did it, not us. And now he's in prison. So, you have no moral right to talk about free media when you do these things.

No, no. It seems like a good argument to me. You do, in fact, lose your moral right to criticize the people for conduct in which you yourself engage. That seems basic. And if you are somebody who likes to spend a lot of time talking about the abuses of foreign governments while being indifferent to or even supportive of very similar abuses by your own – and it's absolutely a similar abuse to imprison Alexei Navalny and Julian Assange. I can make arguments just why they're different in favor of the Russian government but I won’t, let's assume that they're very similar. If you're somebody who does very little about that abuse or other abuses by the U.S. government, including cracking down on whistleblowers, putting January 6 defendants, including nonviolent ones in prison and in solitary confinement for months, even though most of them are not accused of using violence at all; keeping Edward Snowden in exile or refusing to let him come back to the country or step foot outside of Russia upon pain of imprisoning him for his courageous work and showing his fellow citizens how our own government was spying on us without warrants illegally and unconstitutionally, as federal courts in our country have ruled, then I think that argument is very valid that not only do you have no moral credibility, but your attempt to solve those problems elsewhere is severely diminished.

So, as all of those Hollywood liberals clap for themselves, not for Navalny over the filmmakers, but for themselves, for having been so courageous in giving him that award, I think it's very worth thinking about why their focus is so intensely on the bad acts of another government all the way around the other side of the world that our own government tells us to hate, and so rarely on the abuses of our own government.

So that concludes our show for this evening. Remember that we have System Update now available in podcast form on Spotify, Apple and other major platforms published 12 hours after we appear, live, here on Rumble.

Remember as well that every Tuesday and Thursday we have our live aftershow on Locals where we take your questions, respond to your feedback, listen to your ideas and suggestions about who we should interview and what topics we should cover. To join our Locals community, where you also get free access to all of our journalism, just sign up the join button underneath the video on the Rumble page and that will take you to our Locals community, which we are in the process of building even further.

As I said, tomorrow night we will have at 7 p.m. EST, our normal time, David Sachs, who's one of those venture capitalists in Silicon Valley, who was urging and who vehemently defends what the U.S. government did in protecting every penny of the depositors of Silicon Valley. So, you'll get to hear me ask the sort of anti-bailout questions to him to kind of complete the debate that we started tonight with Matt Stoller.

Thank you, as always, for watching. We hope to see you back tomorrow night here and every night at 7 p.m. EST.

Have a great evening, everybody.