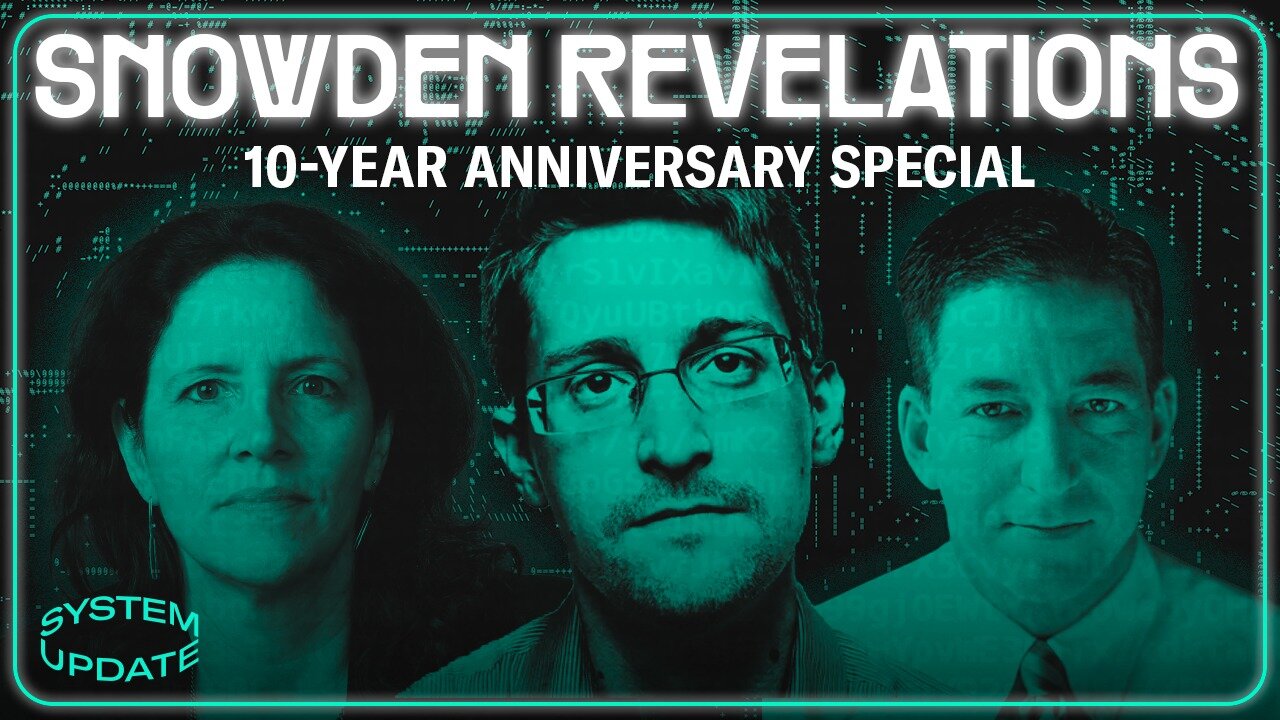

Note: This is part 2 of a two-part piece.

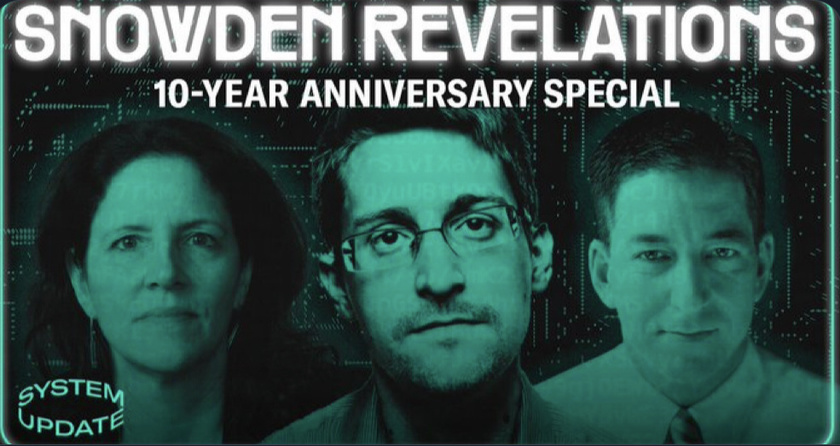

Watch the full episode here:

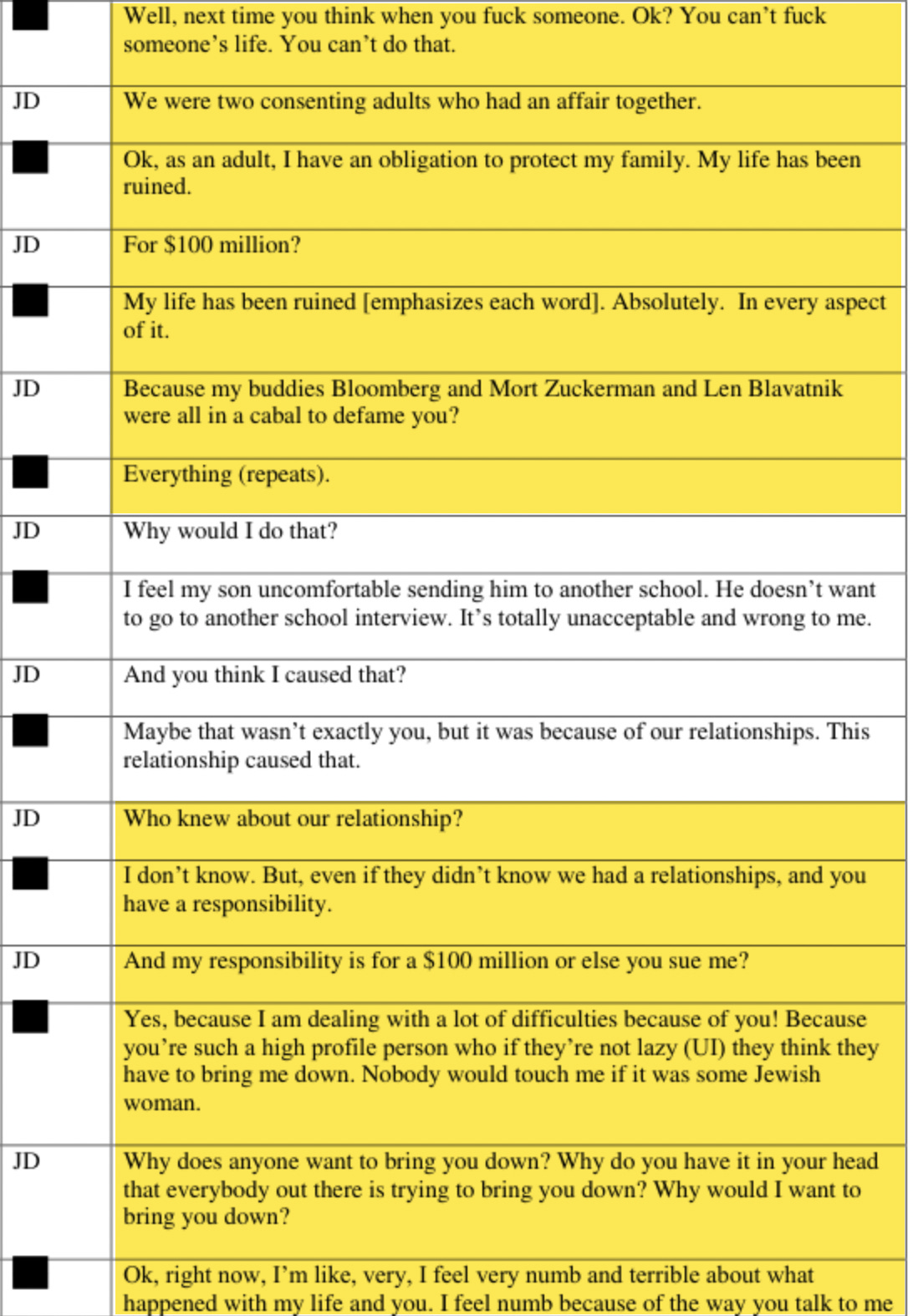

G. Greenwald: All right. Let's talk about this.

(Video. Citizenfour. Praxis Film. 2014.)

Snowden: GCHQ has an internal Wikipedia at the top-secret, super-classified level where anybody working in intelligence can work on anything they want. Yeah, that's what this is. I'm giving it to you. You can make the decisions on that, what's appropriate and what's not. It's going to be documents of different types, pictures, and PowerPoints, and whatnot, and stuff like that.

MacAskill: Sorry. Can I take that seat? Sorry, I’ve got to sort of get you to repeat. These documents they will show…

Snowden: Yeah, there'll be a couple more documents on that. That's only one part, though. Like it talks about Tempura and a little more things. That's the Wiki article itself. It was also talking about a self-developed tool called UDAQ, spelled u-d-a-q. It's their search tool for all the stuff they collect that’s what it looked like. You know, it's going to be projects, it's going to be troubleshooting pages for particular tool…

MacAskill: Thanks. And what’s the next step, when do you think you go public or…?

Snowden: Oh I, I think it's pretty soon, I mean, with the reaction, this escalated more quickly, I think pretty much as soon as they start trying to make this about me, which should be any day now. Yeah, I'll come out just to go ‘Hey, you know, this is not a question of somebody skulking around in the shadows. These are public issues. These are not my issues. You know, these are everybody's issues. And I'm not afraid of you. You know, you’re not going to bully me into silence like you've done to everybody else. And if nobody else is going to do it, I will. And hopefully, when I'm gone, whatever you do to me, there'll be somebody else who will do the same thing.’ It'll be the sort of Internet principle of the Hydra. You know, you can stop one person, but there's going to be seven more of us.

MacAskill: Yeah. Are you getting more nervous?

Snowden: Oh, no, I think, uh, I think the way I look at stress – particularly because I sort of knew this was coming, because I sort of volunteered to walk into it – I'm already sort of familiar with the idea. I'm not worried about it. When somebody like busts in the door, suddenly I'll get nervous and it'll affect me. But until they do, you know, I'm eating a little less. That's the only difference, I think.

G. Greenwald: Let's talk about the issue of when we're going to say who you are.

Snowden: Yeah.

G. Greenwald: This is you know, you have to talk me through this because I have a big worry about this, which is that if we come out and I know that you believe that your detection is inevitable and that it's inevitable imminently, There's, you know, in The New York Times today, Charlie Savage, the fascinating Sherlock Holmes of political reporting, deduced that the fact that there have been these leaks in succession probably means that there's some one person who's decided to leak.

Snowden: Somebody else quoted you as saying it was one of your readers and there's somebody else who put it out.

G. Greenwald: So, you know what I mean? That's fine. I want people to… I want to… I want it to be like, yeah, you know, this is a person. I want to start introducing the concept that this is a person who has a particular set of political objectives about informing the world about what's taking place like, you know, so and keeping it all anonymous. Totally. But I want to start introducing you in that kind of incremental way. But here's the thing: I'm concerned about is that if we come out and say, here's you, this is here's what he did, the whole thing that we talked about, that we're going to basically be doing the government's work for them and we're going to basically be handing them, you know, a confession and helping them identify who found it. I mean, maybe you're right. Maybe they'll find out quickly and maybe they'll know. But is there any possibility that they won't? Are we kind of giving them stuff that we don’t know or […]

Poitras: It's what they know, but they don't want to reveal it because they don’t know or […]

G. Greenwald: Or that they don't know and we're going to be telling them like, is it a possibility that they're going to need like two or three months of uncertainty and we're going to be solving that problem for them? Or – let me just say the “or” part. Maybe it doesn't matter to you. Like maybe you want it. Maybe you're not coming out because you think, inevitably, they're going to catch you and you want to do it first. You're coming out because you want to fucking come out. And you know […]

Snowden: There is that. I mean, that's the thing. I don't want to hide on this and skulk around. I don't think I should have to. Obviously, there are circumstances that are saying that and I think it is powerful to come out and be like, look, I'm not afraid, you know, and I don't think other people should either. You know, I was sitting in the office right next to you last week. You know, we all have a stake in this. This is our country. And the balance of power between the citizenry and the government is becoming that of the ruling and the ruled as opposed to actually the elected and the electorate.

G. Greenwald: Okay. So that's what I need to hear that this is not about…

Snowden: But I do want to say, I don't think there's a case that I'm not going to be discovered in the fullness of time. It's a question of time frame. You're right. It could take them a long time. I don't think it will. But I didn't try to hide the footprint because, again, I intended to come forward.

G. Greenwald: Ok. I'm going to post this morning just a general defense of whistleblowers. That's one. And you in particular, without saying anything about you. I'm going to go post that right when I get back and I'm out. And I'm also doing like a big fuck you to all the people who keep talking about investigations like that. I want that to be I can take the fearlessness and the fuck you to like the bullying tactics has got to be completely pervading everything we do.

Snowden: And I think that's brilliant. I mean, your principles on this, I love, I can't support them enough, because it is it's inverting the model that the government has laid out where people who are trying to say the truth skulk around and they hide in the dark and they quote anonymously. And I say, yes, fuck that…

G. Greenwald: Ok. Let's just so here's the plan then. I mean, and this is the thing. It's like once you – I think we all just felt the fact that this is the right way to do it. It's you feel the power of your choice. You know what I mean? It's like I want that power to be felt in the world. And it is the, I mean, it's the ultimate standing up to that, right, like, I'm not going to fucking hide even for like, one second. I'm going to get right in your face. You don't have to investigate. There's nothing to investigate. Here I am.

G. Greenwald: I think if I had to list the two or three things that most affected me, this would definitely be on that list. I remember when we were in Hong Kong, we always used to kind of joke, and I was a little bit petulant about it, the fact that I wasn't able to sleep for any more than 90 minutes, even using large doses of narcotics that are designed to enable you to sleep. Just the adrenaline and the tension and the kind of excitement and the nervousness just made it impossible for me to sleep. I don't think you were sleeping very much either. And yet, you know, it was always like 10 o’clock at night and would say, every single night, “All right, guys. Well, I think I'm ready to hit the hay,” as though it was like any other day. And I think that for me was the biggest life lesson beyond the lessons about the revelations of surveillance and transparency and whistleblowing and journalism and all the things on which we were focused substantively was that if you are convinced that you have made a choice that comes from the best of motives, you are kind of doing it with a clean conscience and with a sense that what you're doing is just, even in the midst of this kind of extreme turbulence, it provides you a sort of inner tranquility and peace that is both – kind of gives you a sense of resolve, but also a sense of calmness. And I think you can see just in that scene how it kind of becomes contagious. It reinforced our own conduct in the wake of these fears, seeing Ed just so determined in the righteousness of what he was doing. What do you remember about that part of kind of the transcendent lessons that we learn from this?

Laura Poitras: I mean, it was remarkable. It was remarkable from the first day we met him. I mean, that first sort of interview slash interrogation that you did to find out who he was and get all of his backstories. When we went to look at the footage after the fact, he speaks in perfect, perfect paragraphs, with utter calmness.

I mean, it was clear that Ed had made a decision. He'd crossed over a threshold, that there was no going back and he was at peace with whatever was going to happen. And I think we felt that every moment and the fact that we weren't, or that he wasn't more nervous – I mean, you can feel my nervousness like the camera movement and the sort of trying to find focus. I mean, I think, you know, luckily, I sort of had been making films for long enough, sort of my body knows what to do even if my head is like, freaking out. But Ed was completely centered. I mean, he was just completely centered in terms of the choice he had made. And, you know, also looking at these clips, when Ed says things move fast, I mean, I think your ability to turn this information around and report on it so quickly was also one of the things that kept us protected us. I think, you know, we were always one step ahead. And I think the government was probably waiting for the time that they would shut us down or have their own press release and we were just never given the opportunity. And that was because of the work that you were able to do, like after these sorts of filming sessions, to go and report a story every day. We first met on a Monday, the first story came out on a Wednesday and another story came out on Thursday, Friday and Saturday. And then we released a video on Sunday. So that happened in a week. The pace was pretty, pretty intense.

G. Greenwald: Yeah. You mentioned at the start the role that my husband, Dave Miranda, played and the reason that that happened in reality was because he was very suspicious of The Guardian from the start, not necessarily because they were particularly corrupt an institution, but because of this dynamic. I mentioned earlier that the government succeeded, in 2004, in bullying The New York Times from publishing what ultimately became a Pulitzer Prize-winning story about how the NSA was spying on Americans without the warrants required by law and the only reason they had even published it at all was because Jim Wright had had enough and was about to go break the story in his book and they didn't want to be scooped by their own reporter. And David was so sensitive to any – even slight indication that the Guardian might be willing to be bullied or intimidated, that even once they, on Tuesday, said, ‘We just need one more day to talk to the government lawyers and meet with the government lawyers,’ I remember David typing on Skype what he wanted me to say to the editor-in-chief of The Guardian, Janine Gibson – The Guardian in the U.S. – which is basically, if this story isn't published by tomorrow, we're taking our documents and we're going to go just publish them somewhere else. And that's what I mean, like this kind of spirit of how the ethos of how the reporting was done – the kind of determination to do it in the most aggressive way to keep our fears under control – really came from all of us. And it kind of just reinforced each other's resolve.

I just want to ask you about Russia before we watch the third clip that was selected, because, obviously, that is something that's on people's minds when they hear about what you did and where you are. You almost can't have any kind of discussion about politics these days without mentioning Russia. Russia is the place where you have now lived for nine years and, since 2013, it is a place that has provided you essentially effective asylum. And you often say that that was not a place that you chose to be in. You were essentially forced to be there. How is it that you ended up in Russia? And why are you still there now?

Edward Snowden: Yeah. So, if you go back and you look at the contemporaneous reporting, this is all very well documented but basically, I wasn't supposed to stay in Russia. It was a transit route trying to stop en route to Latin America, where because of the openness that South America showed for whistleblowers in the past, particularly in the case of Julian Assange, where they said that even though he's being hunted and desperately persecuted by the United States and the UK and Sweden, he would be welcome to go there. I had talked to a lot of lawyers at this point just in a few days, right? We had to make decisions very quickly because, as you see in the clip, there was a burning fuse where we knew my identity was going to be revealed. It was very likely I would no longer be able to travel onwards.

So immediately we went, all right, I have to get out to a safe place of asylum that's going to be Latin America. We had contacts, we had assurances this would probably be our best bet. I had originally hoped for Europe, but every diplomat that we talked to in Europe basically said this is not going to work like they're going to cave, the government's not going to back you or we'll try, but like no promises. And, you know, it was just very clear from the reporting that everybody in the world knew the United States had raised a gigantic hammer at. [audio problem…] We're like, you know, Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela, Bolivia, they all looked like there were positive possibilities. They had the Caracas convention, or I can't remember which one it is, that was on non-refoulement basically. They didn't extradite people and they mutually respected that. So, there would be free movement. And so, I had a flight that was laid out. The tickets have been seen by journalists. Journalists were on the plane, we were supposed to go Hong Kong, to Russia, Russia - Cuba, Cuba to the final destination in Latin America. It was actually there were forks. There were a couple of different ones that I could go to basically, en route, did we see any response from the U.S. that was going to stop going to one or the other.

But as soon as I left China, it was leaked, and the U.S. government – well, I'm in the air with no communications, headed to Russia – and the U.S. through a whole bunch of sort of emergency press conferences was like ‘Stop him,’ ‘His passport was canceled,’ you know, exactly the kind of thing that we suspected would happen. And so, I land in Russia and the border guards say your passport doesn't work. And I'm like, no, I don't believe this. And I recount the story in my book in great detail. But we basically got Wi-Fi in the business lounge and […] oh, God, they really had done it.

So then, it becomes a long period when I'm actually trying quite hard not to stay in Russia. If you look back at this period – this is what none of these critics say – I spent 40 days trapped in an airport transit lounge where I applied for asylum in, I think, 21 different countries and these are documented. There are public responses from the different countries’ representatives where all – places that you would expect to stand up for human rights and whistleblower protection – places like France, places like Germany, we even went to Italy. Iceland was a big possibility. Where you had one of two responses for the big countries, they went, basically, we won't do this. We won't agree to this because we're afraid of the U.S. response politically, and we just don't want to get engaged in that. If you manage to get here, you can apply with no promises, but you don't have a passport. So, oh, I guess there's nothing that can be done. Good luck with your life.

And then the small countries, that were actually willing to, said “We would do this, but we don't believe we can actually protect you” because of the U.S. practice of “extraordinary rendition,” which is kidnapping – they just send a black-bag team and, of course, or anything, they just snatch somebody up, they put them in the U.S. court system or prison ship or whatever. And U.S. courts have held that this is not a problem, that they can do this but, I mean, that's a whole other story.

And so now, while all of this is happening, we had the Evo Morales incident that you referred to earlier where Bolivia, which had been one of these countries that did telegraph that they would be sort of open to granting the asylum, had their president attend an energy conference in Russia. They had basically heard a rumor or something like that that I was going to be flying back on the presidential plane. And even though the president of the United States on camera, Barack Obama said, “I'm not going to be scrambling jets to get some 29-year-old hacker” literally a week or two earlier, they closed the entire airspace of Europe like a wall to prevent this plane from transiting. And it was a smaller plane because it’s a smaller country and they had to stop to refuel. It lands in Austria, in the airport, and the U.S. ambassador is there to greet it and they won't let the plane take off again – even though this is a president of a sovereign country – until the U.S. ambassador gets walked through and says, “Oh, now there's no guy on here, you know, thanks for helping, you can go now. And that was the moment when it became clear to everyone, including myself, that even if I got a promise of asylum from Germany or France, it wouldn't be safe for me to travel there, because you've got to travel over a lot of vassal states on the air path to get there that they would just close the airspace. And so, at that point, I was out of options. I applied for asylum in Russia. I was granted it. And actually, I've been left alone, remarkably, since then, which is really all that I could ask for given the circumstances.

G. Greenwald: I remember the week after that happened with Evo Morales, I went to the Russian consulate in Rio de Janeiro to get my visa to visit you with Laura. We ended up filming the last scene from Citizenfour there. But also, was the first time I was able to see you since Hong Kong and the Russian consul recognized my name from the application and came out and said to me, “Look, we understand why the U.S. government wants to arrest Snowden. We don't support what he did. We understand why governments need to punish people who leak their secrets but please explain to me why they are so insane like this thing they did, the Evo Morales’ plane is so far outside of – they had no idea that you were even on the plane, It was like a hunch or like a suspicion, and they brought down his plane for that reason alone. It was very dangerous what they did. And even the Russians were shocked at just the extremity of that conduct.

Let me ask both of you, just because this is something that I think about a lot. One of my big concerns before we started the reporting was whether we were going to make the right strategic choices in a way that would generate the attention we thought this story deserved. I remember feeling a huge amount of responsibility that I had just unraveled his life, I was always so worried that I was going to do this reporting. Laura was going to do the reporting. We would end up with like a segment on “Democracy Now!” and maybe a five minute-hit on Chris Hayes and then, that would be the end of the attention and the interest in what we were reporting. As it turned out, obviously the interest and the impact exceeded at least my best-case scenario by many multiples of what I was hoping in terms of attention.

But ten years later, in terms of the reform, I think the kind of expectations or the desires we had about the ability to reestablish the capacity for individuals to use the Internet with some degree of privacy, I'm wondering what you think about the impact of the story from that perspective. It got a ton of attention. It made people aware. People debated Internet privacy for the first time. How do you, though, see now the strength of the U.S. and the Western surveillance state and the ability of people to use the Internet with privacy as compared to before we started the reporting, Laura.

Laura Poitras: I think that that's what Ed did, I mean, his life kind of captures this historical moment where he experienced the Internet as the Internet sort of arrived into our cultures. And I think, as he says, very clearly, it was motivated by the power of that tool for good and for citizens to communicate what an amazing tool the Internet is and how corrupted it's been, how abused has been by governments, and obviously by corporations as well. So, it feels like that's a lost moment, right? I feel that that's people who grow up today don't have that moment of the Internet as a space for free expression. I mean, it's a space that's corporatized, commercialized and it's a surveillance tool. I mean, unfortunately. I do think we, though, have a bit more understanding that there are some tools and technologies that do protect people. I mean, encryption, you know, as of today, it still does work, you know, so that is positive when people know the importance of encryption in a way that they didn't before.

G. Greenwald: But on that, I think a lot of things. One of the things people have forgotten is there was so much momentum in the wake of our reporting, especially about domestic surveillance, that some genuine reform was introduced in the U.S. Congress that was sponsored by Justin Amash, who, at the time was perceived as this kind of hard right Tea Party Republican representative from Michigan, very young, I think he was in his early to mid-thirties who was talking about the Internet in ways very similar to the way Ed was and why it is something we have to kind of protect is this crucial innovation. And he co-sponsored it with John Conyers, the long time, probably on the furthest fringes of the left wing of the Democratic Party as it gets, in terms of mainstream politics. As an African American representative in his eighties, at the time, he was a longtime civil libertarian, and they built a majority in both of the party's caucuses. Foreign Policy has an article that you can read right up today that the headline says, “How Nancy Pelosi Saved NSA Spying Powers.” It was all about how the Obama White House was vehemently opposed to any reforms. And despite Nancy Pelosi to whip enough Democratic votes to oppose this bill and ultimately defeat it by a small number, that was a great opportunity to reform and they had just enough NO votes in the Republican and Democratic parties to defeat it.

There's now a controversy not getting a lot of attention, but some, and I think it deserves more, where the FBI wants to renew one of its most central tools for spying. Section 702, which the NSA also uses, and there seems to be some resistance again in both parties, out of concern that the FBI is basically completely out of control in how it spies on American citizens on the Internet, basically disregards any of the legal constraints that have been put into place, is minimal as they are. Do you have any hope for the ability to at least usher in some real reforms as part of this renewal, or do you think it's just going to, as it always has, so far at least, kind of slide through with just enough votes to continue?

Laura Poitras: Do I have hope in elected officials on either party? Not a lot. I have to say not a lot. But I do think we should use this good article to draw attention to it. I do think we should use this moment to draw attention that this should not be renewed.

G. Greenwald: Yeah. We're going to do a show on that because I think, you know, once you start using words like Section 702, you can kind of hear the clicks of people turning off a program. And so, you know, finding ways to make people understand the personal impact that these things have on them is always the challenge. But we have a lot of practice. It's one of the, you know, kind of central projects, I think, of all of ours, over at least the last decade.

And Ed what about you in terms of this question, obviously there was a huge amount of public attention that I think did exceed our expectations. I remember all the gratification I felt when I would come back to your hotel room in Hong Kong after doing more TV interviews than I could count all over the world and then I got to see you watching the effects of this reporting on your television. I always remember being so relieved and happy that you were able to see the impact in terms of the debate that your decision sparked. And it wasn't just on “Democracy Now!” or on Chris Hayes, but pretty much every global media outlet on the planet was talking about this for months. But in terms of the impact that you were hoping to achieve of reestablishing privacy, of diluting state surveillance, how do you see that 10 years later?

Edward Snowden: Yeah. This was never going to be something like you revealed the documents, and like, in Hollywood, sort of there's sunshine and roses and rainbows the next day. That's not how the world works. That's certainly not how government intelligence agencies work. My desire had been to return public documents to public hands so the public could then express their will and that will would translate into, good or bad, into legislation.

But exactly as you summarized before, we saw the opposite happen. We were doing a lot of polling. I became very close with the American Civil Liberties Union over the months that would follow. They were actually paying for private polling to make sure we had the most accurate information about what the American people, and people globally as well, in other countries, felt about – were these justifiable? When you take the government's strongest arguments into account, would they be supported and we know the facts, actually, the result was no, people wanted to see a change, they wanted to see these programs shut down. They wanted to see this activity behavior stopped. Basically, they just wanted the government and its agencies to comply with the law. And we saw, as you said, legislative efforts in Congress, fairly heroic efforts to make that possible. But then what we saw was the executive hijack the process – a task someone like, you know, a Nancy Pelosi type, who was personally implicated, by the way, in the criminal activities that were being revealed and discussed, for a long time, because she had previously been top dog on the intelligence committees and they basically thwarted the public desires and they knew what they were doing. They used proceduralism. They used deception. They used the kind of misinformation and disinformation that's becoming so talked about as the threat today, anything they could do to try to bury this. But that's kind of how it works. And that's the meta-angle of this story that you see in what I'm talking about.

The remarkable thing about the early Internet is that you could have a child engage with an expert on equal terms. And it was the argument that was assessed and valued and measured rather than the identity because the identity wasn't known. They had both chosen their own names. They had both chosen to engage in the conversation. The kid, surely, nine out of ten times would be wrong but maybe one time they were right. They had a good point. The Internet and governance, conversation, debate, policy have become very identitarian. The Internet has become very identitarian. Both corporations and governments heavily pressure these sorts of a real name, real identity policies, where they want you to put your picture up there. They want you to put your face up there, they want you to put your name up there, and people end up pigeonholed. Their filter bubbled into little communities and even where they are sort of radical, or out there, they're shouting into a small void only occupied by people of like minds. And this is how the democratic process went sideways. And this is kind of what's happening or likely to happen with this approach to (section) 702 reform at the end of the year. You know, it's ironic that […] Go ahead.

G. Greenwald: Let me just introduce just a quick question, which is when I started seeing some of the footage from Citizenfour, that Laura took, and then when I watched the film and kind of just had some opportunity to breathe and reflect on what we did in Hong Kong, I ended up realizing that probably half of what we talked about was about the privacy aspect and the surveillance aspect, but probably half of it was about the role of journalism and the importance of transparency. The fact that if we're going to turn the Internet into what it was promised to be, which was this unprecedented tool of liberation, into the opposite, which is the most unprecedented tool of coercion and control through surveillance, that it ought to be at least something in a democratic society that we know about, that it's not done in secret. Even unbeknownst to many of our elected officials, we had members of parliament in the U.K. and members of Congress in the U.S. saying they had no idea any of this was being done until they learned about it from the reporting that we did and that your whistleblowing enabled. I think people look back at the story and think about it as being about privacy and surveillance, which of course it was. But what about the journalism and the transparency component of it? That was clearly a pretty big motivating factor for you as well.

Edward Snowden: Yeah. I've been saying for 10 years now, like the reason that I didn't go to the New York Times, was the fact that they spiked a story one month before an election that would have changed the course of that election – that President Bush had broken the law and spied on every American, violated the Constitution the most flagrant way – and they were like, “yeah, the White House doesn't want us to do that, so, we're not going to do that.” And it's The New York Times, right? You would not think it to be the most pro-Bush organization. The reality is the distance between the left and the right institutionally is not very far. When you talk social issues, there are differences, right? Well, when you talk about the kind of thing they put on a bumper sticker, there are differences but when you talk about institutions, when you start talking about money, when you start talking about violence, when you start talking about power, they're really largely marching in lockstep there.

What we saw in 2013, and the years after it, is that this is not a story about surveillance. It's a story that involves surveillance. This is a story about democracy and power – how institutions function and what we are taught to believe is a free and open society. But it will not and never can remain a free and open society unless we make it so. And we must make it so over the objections of the government. And that's something that I think a lot of people don't understand. I have been criticized as a hacker, right? To imply some sort of criminal cast on that. But what is a hacker? People think like Stock photos of some guy in a hoodie hunched over a keyboard. But a hacker is simply somebody who understands the rules of a system better than the people who created it. Hacks are the product of exploiting the gap in awareness between how the system is believed to function and how the system functions, in fact. And that's what's happened to our political system, not just for the last 10 years, but for the last many, many decades, where the public wants one thing, the public believes one thing, it's very clear there's support for one thing, but then, special interests or corporations or lobbyists or a party or both parties want something very different. Look at this: even just considering the way stock trading is handled for members of Congress, everybody in the country is getting poorer while they are becoming richer. And when you look at this, when you look at the story of 2013, when you look at the reforms that happened and the ones that don't, a lot of people fall into despondency, they become depressed. They think there's nothing we can do, but actually, we can, and we did. The important lesson to take away from 2013 is not that, “Oh, you know, the sort of bad guy was vanquished and everything is good again,” because that's not how it works. This is the work of a lifetime. This is the work of every lifetime. If you want a free society, you have to make it that way. But just like these institutions, hacked our government is to seize control away from us, in important ways, small groups of committed people, activists, volunteers, engineers, and people who have no political power whatsoever, coordinated and collaborated together to hack the Internet in a positive way, to defeat the very forms of mass surveillance that the government was doing without the public will on a technical level. This is the kind of thing we're talking about with encryption. In 2013, nobody used secure messengers unless they were, you know, cypherpunks, so, unless they were hackers, unless they were information […]

G. Greenwald: Somebody on the U.S. government enemies’ list, Iike Gora. I think let me just say, it's really true, you know, obviously, I did not know how encryption worked when we first spoke. It wasn't something I was particularly talented at mastering, but I remember very well within the first month of the story, or two months after the story broke, several New York Times journalists, including some of the most well-known investigative journalists who work on the most sensitive national security matters, kind of called me with an attitude of sort of like, okay, we'll take it over from here. Why don't you go ahead and give us the archive and we'll go ahead and do the reporting and then, you know what? I made very clear that wasn't going to happen, that we were not going to just send them a copy of the archive because they were entitled to it, because it’s The New York Times, it started becoming a kind of like pleading sort of, can you please share one or two stories with us? And as we considered it, you know, I made very clear to them that using the most sophisticated forms of encryption that I had taken like a three-month course in, was a prerequisite to even considering that, and almost none of them knew what encryption was, seen with reporters at The Atlantic, The New Yorker, and just the fact now that we can talk about encryption, it's something that people are aware of. People use signals and purposely seek out privacy-enhanced means of communicating. All came from this report. None of that was true prior to 2013. I think you two were among 14 people on the planet that use encryption back then, and now, it's something that, maybe is not as common as we want, but infinitely more common than it was back then.

Edward Snowden: That's absolutely right. Everybody who works in the news nowadays uses encryption. One of the – actually the only sort of public example of the damage that all of us collectively produced as a result of these disclosures – that was publicly argued by then Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, most famous for lying to Congress – was that the revelations of 2013 about mass surveillance pulled forward the adoption of strong encryption on the Internet by seven years. And he said this on the sidelines of the Aspen Security Conference to reporters and he was like, this is like a terrible thing, like “oh, no”. This is one of the nicest things anyone's ever said about me. Like, this is a remarkable thing. Like, we made global communications more secure by seven years. A lot happens in seven years.

G. Greenwald: Absolutely. So, we're going to talk about this third clip. You know, we've spent time talking about the significant risks that were in the air from this reporting, not as a means of congratulating ourselves for our great personal courage, but in order to illustrate how many tools Western governments have to punish people and to try and intimidate them if you actually do real reporting that undermines their interest – if you expose the lies and illegalities they do in secret. WikiLeaks was certainly hanging in there the entire time that we were doing this reporting.

The first time I met Laura was when you came to Rio. You were working on a film about WikiLeaks at the time and came to interview me as part of that film. The fact that they were being persecuted back then was certainly something that was very much on our minds. And then once we did the reporting, the threats that people like James Clapper were making, both privately and publicly, the U.K. invading the newsroom of The Guardian and forcing them through threat to destroy those computers, although it was something the Guardian, I think quite cowardly, ended up acquiescing to unnecessarily. It was a pathetic image to see The Guardian destroying their own computers while government agents stood over them, instead of forcing them to go to court and getting an order to force them to do that. And then, the other episode was the detention of my husband, David Miranda, when he had gone to visit you in Germany and was traveling back to Rio through Heathrow International Airport and was detained for 12 hours under a terrorism law. I remember that day very vividly, and the only reason I believe he got released was because the Brazilian government, under Dilma Rousseff, was very aggressive about demanding his release. It became a big diplomatic scandal between the UK and Brazil. It was the biggest story in Brazil that the British government obviously picked David in large part because he was Brazilian. You would travel out of Heathrow, in and out of Heathrow, without problems, even though you actually had a government watch list for the United States. And so, this scene from Citizenfour is when they did release him. And I went to the airport at 4:30 in the morning to get him. And there was a huge throng of international media there. And you had sent somebody to film that scene and it became part of Citizenfour. Do you want to talk about the clip before we show it?

Laura Poitras: First of all, sort of going back to sort of the larger context. I mean, like in the work that I do, I think just important and it's also the work that both of you talk about – the sort of the myth of American exceptionalism that we go around saying that we care about press freedom and yet we're trying to put Julian Assange in prison for the rest of his life. And the importance of constantly talking about that. And one of the tools and techniques that the government uses when they want to target journalism that they don't like or criminalize journalism that they don't like is to use the label of terrorism. So, I know that very well. I was put on a terrorist watch list in 2016 after making a film about the war in Iraq, and this is what the UK did when it detained David.

David had come to Berlin to work with me. I'm not going to go into a lot of details because it's not something I do often but it's true that I didn't trust many people and I trusted David and I wasn't going to trust anyone else. But I know now, in retrospect, I have no doubt that there weren't multiple intelligence agencies following every step of his travels, and they were just looking for the right moment to target him. I'm sure that they were in Berlin and I'm not going to speak to The Guardian's decision to route his flight through London but it's true. I'd already been there. And I think it's just a reminder that so many people made this reporting possible, not just the people whose names are out front. My name, your name, Glenn. So many people took enormous risks. And David really took an incredible risk as somebody who wasn't holding a U.S. passport and was taking enormous risks, too, to enable this journalism with no personal benefit and only personal risk. And I'm forever grateful to him.

G. Greenwald: All right, Let's show this clip.

(Video. Citizenfour. Praxis Film. 2014.)

[Text on Screen]: On his return to meeting me in Berlin, Glenn Greenwald’s partner, David Miranda, is detained at London’s Heathrow Airport for nine hours under the UK’s Terrorism Act.

The White House is notified in advance.

Greenwald: Oh, my God. David! You. You’re ok?

(They have to cross a hall crowded with reporters)

Miranda: I just want to go.

Greenwald: Okay. Okay. Okay. You just have to walk through it.

(In elevator)

Miranda: How are you?

Greenwald: Good. Good. I’m totally fine. I didn’t sleep at all. I couldn’t sleep.

G. Greenwald: That really reminds me of when that happened, we both felt an obligation to present this very defiant and fearless posture because we wanted it to be very clear that the attempt to intimidate us in our reporting was not going to work, that that we were not in any way frightened by what had happened. We weren't bothered by it. This was something we felt very important to convey. And yet over time, David started to acknowledge, first to me and then to himself, that in fact, it was very, very traumatizing because – and this is something that I didn't think about at the time, and I found it so interesting that I didn't – which was that I think if you do hold an American passport, as you said Laura, or you just feel like you're kind of in a way protected. But, you know, he talked about the fact that if you're someone who's not white and you don't have a British or an American passport and you are accused of violating terrorism laws in the U.K. or the U.S., the governments have proven that there is no limit on what they will do to you. And he spent that day, you know, imagining things like being taken to Guantanamo or, not necessarily the most rational things, but with a good component of rationality to them.

I remember I'll never forget the British official who called me that day and said David had been detained under a terrorism law. The first thing I did was go immediately online and found both of you. I don't remember in which order, but I do remember, Ed, that I don't think I've ever seen you as angry as you were that day. Neither before nor since, because there was just something about it that was so, you know, it really revealed exactly the reasons why these governments can't be trusted with these kinds of powers – and just like the abusive and thuggish nature of what they will do. Why was that something that I mean, you've talked about, the admiration that you've had for David many times, but why was that day in particular something that was just very emotional for you?

Edward Snowden: First, I remember getting sort of a live update from you. And when David was finally released and you had communications of the breakdown of what had happened and how it was and, I mean, I was just extraordinarily impressed by his courage, which was almost otherworldly at one point. He's in interrogation with terrorism officers, Lord knows how many spies are in a cell in Heathrow. And, you know, they're like, oh, you know, do you want some water or something like that? And the guy's got to be parched. And he's like, I don't trust your water. And the message that sends and just the human desire to escape the situation just even for five minutes, the pressure to say, yes, please, give me something. He didn't give an inch. You know, that's an example that will stay with me for the rest of my life. But this is something that I had to deal with many times where I was like, what are they going to do with my family and people traveling to meet with me? It was just so greasy and underhanded to intercept somebody who was a family member of a journalist, working on this directly traveling in the service of a journalistic task, in a journalistic role, on a ticket that's funded by a newspaper. And they knew this, they knew this, but they didn't care. And that was the point like that, the whole thing where they're like they notified the White House in advance. They're clearly coordinating. A decision was made at the very highest levels because they knew the implications of this and they went, what can we get? How far can we push? Will this person cooperate? Is this something that we want to repeat? And it's important for people to understand, I think, the power of not cooperating and sending the example that this is not going to go down the way you think it is. And I think the world owes David a debt of gratitude. He is a remarkable man, a good friend. But most importantly, he was a good person who did good work for all of us.

G. Greenwald: And so, as kind of the last question, we've talked about him a couple of times, but I do want to conclude by talking about Daniel Ellsberg, because this was somebody who, for me was one of my childhood heroes. And the fact that I was able to become a friend of his and then work with him at his side and yours, both of you, in the organization we created back in 2011, the Freedom of the Press Foundation, which originally was about trying to break the blockade that the government had pressured corporations like Bank of America, MasterCard, Visa and Amazon from essentially excluding WikiLeaks from the financial system to prevent them from fundraising – an incredibly dangerous power to give the government extrajudicially with no charges just to cut off their funding – and now it's expanded to become a very broad-based press freedom group.

The ability to have gotten to work with Daniel Ellsberg for me was one of the great honors of my life. I kind of consider him the pioneer, like the grandfather of modern-day whistleblowing, you know, this kind of large-scale, full disclosure of the way the government keeps secrets in order not to protect American people but to protect themselves from the lying and the lawbreaking that they do. Clearly, I think I can speak on behalf of us, he inspired us in all sorts of ways. I know he did for me. He was widely reported to have terminal pancreatic cancer. He's at the kind of end stage of his life. So, both in terms of like what he meant for the story, but also just like the impact that he had on the world Laura, what do you see as his kind of legacy?

Laura Poitras: And it was a good example of a bit of a whistleblower doing the right thing, Somebody who was exposed to knowledge that he knew that the public had a right to know. And I do think often that it shouldn't be the case that whistleblowers like Ed and Dan and Chelsea have to risk their lives for us to know what we've learned from them, that we know that our elected officials actually had the protection. They could go and read anything into the public record and face no political consequences because of their position as elected officials. And yet they refuse to do the right thing. For instance, anyone who was elected in Congress could release that classified torture report, just released into the public, read it into the public record, and they don't. And it's really, it's not a good sign of a society that people like Ed and Dan have to take the risks that they do when we have people in elected leaders, so-called leaders, who could do that and face very little consequences criminally.

G. Greenwald: Yeah, just along those lines, before I ask you at that same question, I do think it's worth remembering, first of all, before Daniel Ellsberg went to The New York Times and gave those documents to The New York Times, he tried to get senators to use their constitutional immunity that essentially says that members of Congress can never be held accountable for anything they say on the floor of the House or the Senate to read the Pentagon Papers into the record, knowing they could not be held accountable. And they refused to do it and forced him into the position of committing what the government regarded as felonies. And he almost went to prison for it. There was something very similar, which is two members of Congress – Ron Wyden and I forget the other Democratic senator now, I don't know if you guys remember, you can tell me [...]

Edward Snowden: […] Senator Udall.

G. Greenwald: Yeah. Senator Udall. Udall. Yeah, exactly. Wyden and Senator Udall went around for two or three years hinting and winking and saying, “Oh, if you only knew what the NSA was doing in terms of their interpretation of the Patriot Act and what powers they claim for themselves, this would shock you,” but they would never say what it was, even though they had that same power to go on to the Senate floor and talk about it without any consequences at all – or leaving it to Ed to risk his liberty, which he did – he could have easily ended up in prison and probably the odds were overwhelming that he would have, but instead end up, you know, now nine years in exile [...]

Edward Snowden: And may still.

G. Greenwald: And you still might. Exactly. And that risk is still there. Hopefully, it's not going to happen. But they left it to you to go and do, and exactly as were said, it is the failure ultimately of people in power that leave it to ordinary citizens, who are defenseless, to go and do what they should be doing themselves. That's how Daniel Ellsberg came very close to life in prison. That's how Ed did as well.

So, in terms of Daniel Ellsberg, who I definitely see as your predecessor, he always said that he regarded people like you and Chelsea Manning and Julian Assange as people he was waiting for his whole life to kind of emerge as people who did exactly what he did in the same spirit. He's long been one of your most vocal defenders from the beginning. How do you see his legacy and his life at this stage?

Edward Snowden: Dan is a dear, dear friend of mine. But when you scope out of the personal, the remarkable thing about Daniel Ellsberg is he became an archetype. He established the archetype. There will probably never be another Daniel Ellsberg, but there will be many, many people who follow his example. And I am absolutely one of them. I do not believe I could have done what I did without the example of Daniel Ellsberg. When I was agonizing over what to do – Should I say anything? How should I manage this? – I watched a documentary, which is a beautiful callback to Laura's involvement, called “The Most Dangerous Man in America.” And just seeing his example, how the White House villainized him and said all the worst things – they immediately went after him. They used the media. They used dirty tricks. It provided just the bare outlines of a template that I would continue to flesh out, look at and revisit and poke at, and modernize something to work from a sketch of how it should be. What are people at their best? Daniel Ellsberg, when he released the Pentagon Papers, was a man at his best.

One of the things that struck me, when we talked about the Russia thing and everything like that, that was when everybody was starting to freak out about that for the very first time, in the beginning, and saying I should come home, I should come home, I should go to the courts, Daniel Ellsberg came forward – and he had never spoken with me at that time – and he said, “No, absolutely not.” The United States of 2013 is not the United States of the 1970s. Our court system provides no meaningful defense against this. He'll be convicted. The story will shut down, he won't be able to argue his case. The jury won't be able to decide the central questions. The truth won't even be allowed to be spoken in the court because the government will object and the judge will sustain it and that's how the system works today.

I think the most consequential thing about Dan, in his life, and his example is that he allowed us to scope out from that individual to look at the systemic problem through his example. He actually provoked the state into revealing itself for what it is, which is an entity that will stop at nothing, frankly, to preserve its own power. It's not about national security and it's not about homeland security. That's rhetoric. It's about state security, which is a very different thing for public safety. He taught me that. And I think we'll be learning from his example for a very long time.

G. Greenwald: Absolutely. And from yours. And so, I just want to say I went into journalism to do stories like the one we did together, where you fulfill your function, you as a citizen. Laura and I, as journalists in this case. You discovered deceit and abuse of power by the most powerful people in society and then you used journalism and whistleblowing in order to expose it, to inform the public of things that should never have been kept from them. In the beginning, I do think it ushered in a huge amount of change, even though the NSA is still –the building has not collapsed in on itself – they are still spying.

I think the example that you set as a whistleblower, that the film inspired, that we were able to do in terms of re-establishing the spirit of what journalism is supposed to be about is, one of the great honors of my life. It's one of the things of which I'm proudest 10 years later, more so than ever. And the fact that, even though, as Laura said, we did do it with a large number of people without whom it really would not have been possible, it began with the three of us in that hotel room in Hong Kong. And I'm very honored that I got to do it together with the two of you people whom I really admire and whose integrity and courage I have immense respect for. And so, I'm thrilled we got to do that together until we got to spend this 10-year anniversary together talking about it and talking about the implications of it. And I really just want to thank you for taking the time.

Edward Snowden: It's been an absolute pleasure and I hope we can do it again in 10 more.

G. Greenwald: Absolutely. Our 20-year anniversary – it's kind of like those high school reunions where every 10 years everyone gets a little older, but you still forge ahead with it. Great to see you guys. Thanks so much.

Laura Poitras: Thank you so much.

Edward Snowden: A pleasure. Cheers.