Watch the full episode HERE

NOTE: Due to technical difficulties, this transcribed interview was released later than 24 hours after airing. Thank you for your understanding!

The Interview: Prof. Ivan Katchanovski

As I said at the top of the show, professor Katchanovski has been one of the most reliable sources for news and analysis since the start of the war in Ukraine. A scholar in Russian studies and in that region, he now teaches at the School of Political Studies and Conflict Studies in the Human Rights Program at the University of Ottawa. He's been a visiting scholar at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard. He has written books on post-Soviet Ukraine and has been cited as an expert on the conflicts in that region and Ukraine in media outlets throughout the world. He was also the person who essentially broke the story that you probably remember that the Ukrainian Canadian man, who was honored and cheered by the Canadian parliament led by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau with President Zelenskyy at his side, was a Nazi SS soldier during World War II, something that was not just embarrassing, but highlighted the optic gnawed problem of the presence of neo-Nazi factions in Ukraine. As I said, I've been informed about this war by him as much as anyone else, and we are thrilled to welcome him tonight for his debut appearance on System Update to discuss the latest defeats and problems for Ukraine and the West, the serious and growing challenges of Ukrainian recruitment and where this war is and will likely go.

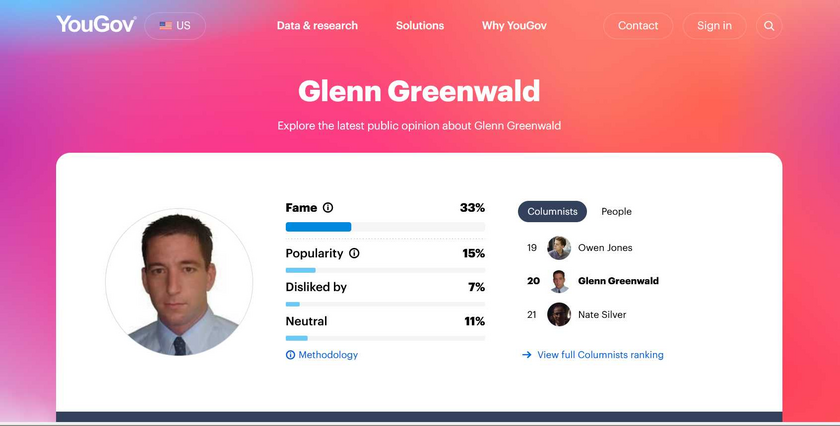

G. Greenwald: Professor, thank you so much for joining us. It is great to talk to you. I've been following your work for a long time and I'm glad to finally speak with you.

Prof. Katchanovski: Thank you for the invitation. It's a pleasure to be on your show, which is very important and a great source of information about different issues, in particular about the war in Ukraine.

G. Greenwald: Absolutely. I couldn't agree more. And I want us to start before we get into the substance because there are so many people who seem to have become overnight experts in this region, whereas it seems to me like a lot of them couldn't have placed Ukraine on the map before this conflict who pontificate on all sorts of things. Can you talk about the basis of your studies and interests in and expertise about Ukraine and this region?

Prof. Katchanovski: Yes. I’m originally from Ukraine, from the western part of Ukraine. I studied Ukrainian politics since I did my dissertation in the United States at George Mason University on regional political divisions in politics in Ukraine and Moldova, and I have specialized in politics in Ukraine since that time. For a very long time, I researched the conflicts in Ukraine because I view this as a very important issue, not only to Ukraine but also to other countries. And now I think we witness such a development, in terms of war in Ukraine, which has an effect not only on Ukraine but also on many other countries, including the United States, because this war [has] now become a proxy war between Russia and the West in Ukraine, in addition to being the war between Russia and Ukraine.

I also published four books based on my research and 20 peer-reviewed journal articles. Just today I finished another book manuscript, a manuscript on the Maidan massacre in Ukraine, which I submitted to a major Western Academic Press for publication. So, I specialized in assessing Ukrainian politics and specifically, on conflicts in Ukraine for a very long time. And I do this not relying on the media because – I think this is a very important distinction – because if people just view the Ukraine war via The New York Times coverage or NPR or any other Western major media, they will have a very biased perspective and very one-sided view of Ukraine and the war in Ukraine. And I think it's very important to rely on many sources, on Ukrainian sources. And I published some of them in the media, on my social media and Twitter. And I said this, each day I view hundreds and hundreds of videos. I read different sources in Ukrainian and Russian, which is another major language in Ukraine, so I think this is very important, to have perspective and to hear some kind of Ukrainian voices, which are very limited in terms of their representation in the Western media. And I can say that just there are few political scientists in the world who are actually able to do such research because very few of us have, you know, Ukrainian language and Russian language, which are required for such research. I think this is a very important issue to research. I think the media in this regard is not a very good source of information, to say it mildly. I also researched, Western media coverage of Ukraine before this conflict started, and I think this is a very important issue and perspective, which is often lacking, by the media, in particular, concerning Ukraine, not only Ukraine, but also other countries as well.

G. Greenwald: Congratulations on the completion of that manuscript. I think it's so interesting because social media in general, Twitter in particular, is often maligned as a place where misinformation is spread. At the same time, I think one of the most important benefits of it, is that it enables people like yourself with real expertise, who would not be given access to a lot of mainstream places in Western media to find an audience, to be heard, and to challenge a lot of the orthodoxies. It's one of the ways that I discovered your work, and it kind of shows just how important it is for people like you to be willing to use those platforms to be heard.

Let me ask you about the war itself because talking about Western media and this kind of closed information system and said the New York Times and NBC News, for the first year of the war, it was forbidden to suggest that Ukraine would have difficulty in this war against Russia. Some early successes surprised people that the Ukrainians had against the Russian military but now, sort of two and a half years into the war, even the Western press that would never have allowed this kind of claim two years ago is really admitting that essentially the Russians are winning the war, that they're advancing rapidly, the Ukrainians haven't been able to gain any control, any territory, that their front line is increasingly fragile and endangered. What do you make of where the war is and where it's likely to go? Just in terms of the battlefield.

Prof. Katchanovski: I think it was very clear from the start of this war that Ukraine has no real chance of defeating Russia, and this has not changed since, any events that took place in Ukraine, including Russia's withdrawal from the Kyiv area, again, in March and April of 2022, after this peace agreement was very close to being signed by Ukraine and Russia to end this war. But this peace agreement was blocked by the Western countries and those leader such as Boris Johnson and the Biden. And I think this was the main reason for Russia to withdrawal their forces from the Kiev area. I watched these battles taking place in the Kiev area on social media via different Telegram channels. There were many videos. Originally, I also studied in Kyiv, at my university, before I came to the United States. So, in this case, I think it was very clear that this was not a military defeat of Russia. So, the Russians just basically – even though they had very significant resistance from Ukrainian forces – decided to withdraw from the Kiev area because of this peace agreement, which was very close to being signed. And I think a lot of media just use this withdrawal of Russian forces, as evidence that Ukraine was defeating Russia, that Ukraine is winning this war, even when this wasn’t the case. And the same thing happened with Avdiivka withdrawals of Russian forces and the UK was able to take back territory which was defended by Russian forces in the Kharkiv area. And now Russia basically launched a new offensive in this region and was able to capture some parts of the Ukrainian territory in the Kharkiv region. But it was very clear, and from the start of this war, I pointed to this on Twitter, in academic studies, and also in my media interviews that Ukraine has close to zero chance to defeat Russia. It was clear that Zelenskyy and his partners in the United States, the Biden administration, basically gambled against all the odds of defeating Russia even so, there was no real possibility. And I regard this as a major folly, as a major mistake. I think this was a mistake for many people but I think this is kind of a villainy. They wanted specifically to use Ukraine as a tool to defeat Russia – not to defeat, but actually to weaken Russia, as a current head of the Pentagon stated in the spring of 2022. So, they did not believe that Russia could be defeated, but they presented this as propaganda that this can be achieved in order to justify such a policy, which I think has a damaging effect on Ukraine. And based on my research, I think this is just a misinformation issue – not social media – actually politicians and governments and also mainstream media, which are major sources of misinformation because they have vested interests to misrepresent, for their political interests or their business interests or personal interests. What's going on – and I think in this case, academic research is very important, I tell you, just to present the picture, which is, based on evidence and the facts and not on the kind of political, wishful thinking or any kind of political biases.

G. Greenwald: I want to get a little bit more into the motives of the West and NATO concerning this war. But before we get to that, one of the tactics that the Western media, and especially the American media, has used for a long time to sell wars is that they will make claims about what the people in that country believe or want by handpicking a certain group of people who represent not necessarily the views of the whole country, but the views that the West wants to hear. This was a famous and well-used tactic before the war in Iraq. We heard from all these Iraqi exiles who hadn't lived in Iraq for 40 years, who were presented as speaking for the Iraqi people who said Iraqis hated Saddam Hussein and they wanted the West to come in and overthrow them and be welcomed as liberators. The same thing in Libya and Syria, it's a sort of tactic that's done all the time. And one of the things that have happened since the beginning of this war is that we're constantly being told how much Ukrainians love their central government in Kiev, how much they support Zelenskyy, how much they hate Russia and the Russian invasion, because we basically only hear from people in the parts of Ukraine that are anti-Russian, in Kiev and the western provinces, and we basically never from Ukrainians who live in, certainly, in Crimea or in the eastern provinces, who have a different view. Can you talk about the difference in perspective, identity, and history between these two parts of Ukraine?

Prof. Katchanovski: Yes. I published a book on this very topic based on my doctoral dissertation, at George Mason University, in the U.S., and I can say that Ukraine was a divided country, between the eastern part and the southern part of Ukraine, which was Russian. And because they used to be part of Russia for a very long time, for centuries, while western Ukraine and to a lesser extent, central, you have a different history. Western Ukraine was, for a long time, part of Poland or the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After World War I, it became a part of Romania and Czechoslovakia, and only as a result of World War II western Ukraine was incorporated into Soviet Ukraine under Joseph Stalin. So, in this regard, it was a very divided country because people in western Ukraine were very pro-Western but also pro-nationalist, and they were also very anti-Russian, in contrast with people in eastern and southern Ukraine. But, it's also very important to understand that pro-Russians who lived in eastern and central Ukraine did not necessarily support the invasion of Ukraine or a desire basically to be part of Russia. According to my research – and according to a variety of public opinion polls – the only two regions, Crimea and Donbas have a majority support for seceding from Ukraine and joining Russia. These two regions, including the ethnic Russians, who were the majority of the population in Crimea, and also a cluster of 50% of the population of Donbas support the current war by Russia in Ukraine. You can say also support the cession of the regions or joining Russia. While people in the West of Ukraine also to a large extent, in central Ukraine and Kiev city in particular, support joining the European Union and NATO.

So, there was such a very significant divide and this divide was manifested in all elections since Ukraine became independent, in 1991, but public opinion polls also show a similar divide because, the majority of people in the West said they wanted to join the European Union, they wanted to join NATO. But the people in eastern Ukraine and southern Ukraine were against this. And now a lot of – again, the media now uses public opinion polls to say what people actually in Ukraine think about the war or peace agreements, they say that people in Ukraine are actually against a peace deal with Russia to end this war. But now, public opinion polls are not reliable because Ukraine now become even less democratic [than] it used to be before the war, basically, it's not a democracy anymore. There is no free press, there is no possibility to express political opinions freely because of the passive policies of Zelenskyy’s government. So only people actually able to express opinion in Ukraine now are people who support Zelenskyy’s government and people who have different views, actually are not able to do this. Many of them are even in prison, if they criticize, or say something, which goes against the current policies. So, in this case, I think, the voices that are present in the Western media of Ukrainians who support this war, the continuation of this war, and claim that they support Zelenskyy’s government, and his policies, actually are often not representative of all Ukrainians in Ukraine. They are very biased. And a lot of people who speak very good English, again, are interviewed very often in the media as talking on behalf of all Ukrainians, but actually they're not talking about all Ukrainians. They often talk about themselves or their narrow elite views, or often just people from western Ukraine and Central Ukraine also, to a significant extent. They are giving only limited or very insignificant media coverage, while people who have different views, including myself – I'm originally from western Ukraine and I supported, again, from the start, I supported joining European Union membership for Ukraine. But it's very difficult to get my views expressed in the media, Western media in the United States, actually, now, since the Russian invasion – even if I gave a few thousand media interviews in different media of more than 80 countries of the world – basically all mainstream media in the United States, now, basically did not ask me for any interview, since the start of the Russian invasion. And I think this is just a manifestation of the problem, because the kind of representations that people are giving in the media, including also very prominent media like the New York Times, are often biased and not representative of the views of Ukrainians. It’s very important because, if you look into a variety of public opinion polls – they are often cited by the media as evidence of the main view of Ukrainians – but public opinion polls now are not reliable because people are not able to express how they feel. I do not use public opinion polls. I look into the behavior of people because what people actually do is a much bigger kind of manifestation of their actual views compared to what they say, especially if they feel pressured to say what actually would be regarded as politically acceptable, which often people do now in Ukraine.

G. Greenwald: So one of the ways that we can see some dissent, I guess you can call it, from the war policies of Ukraine, is something you've been reporting on and discussing a lot of and showing videos, a lot of, which is the growing number of Ukrainian men who are physically resisting, not just hiding, but when they're found, physically resisting the Ukrainian military recruiters who are trying to take them and force them to enlist in the military and then fight in the front line. There was a BBC report from a month ago or so that said, since the start of the war, something like 650,000 Ukrainian men have left the country, have fled the country, have found a way out of the country, presumably to avoid the war. Do you think that this trend that you're showing is a growing trend among Ukrainian men resisting being drafted? And if so, why is that growing? Video 1. Video 2. Video 3. (Forced Conscription in Ukraine.)

Prof. Katchanovski: Yes. These are exactly the videos that you just saw were from different regions of Ukraine. One of them was filmed in the native region of Dnipro [center of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast] near southern Ukraine or eastern Ukraine, which is Zelenskyy’s native region. The other video was from Kiev city and another video was actually from the Rivne region in western Ukraine, which is a very anti-Russian region. And in all these regions, basically in all these different locations of Ukraine, people try to escape and evade [drafting] specifically because they are caught by police or by military recruiters on the street, then they are sent to a front line with a very insignificant amount of training and without any skills, and many people get killed. So, I looked into such evidence. I analyzed this video on social media. I watch hundreds of videos each day, and I only post a very limited amount of the videos because this is enough – that's what I find, this part of my research – just representative videos I put it essentially, which received also a lot of attention.

But I can say that the number of such videos has increased very significantly since the new mobilization law was announced by Zelenskyy, two weeks ago. They show that there is very significant resistance to forced mobilization to continue this war by people not only in eastern and southern Ukraine but also people in western Ukraine and the people in central Ukraine. And this is not only based on the videos, because if you look into statistics, in addition to the number of people which are mentioned in this BBC report, which you cited – 650,000, who left Ukraine – actually, according to a statement by a former advisor to President Zelenskyy, who actually said in one of his media interviews that, 4.5 million Ukrainian men resisted updating their information in military equipment offices because they did not want to be called for the military to be conscripted to the military service. So, 4.5 million Ukrainians resisted doing this voluntarily and now they face very significant punishment in terms of very significant fines and even the possibility of confiscation of property, even imprisonment if they continue not registering their information to community recruitment offices.

If you're looking for other kinds of sources of information, there was an interview by one of the officials from Rivne again in western Ukraine, which is a very anti-Russian region, who said that recently just 2% of people who were “summoned” to military court, come voluntarily. So, this means 98% of people in the most anti-Russian region of Ukraine do not want to do this. And, according to some Ukrainian media reports, actually more than 1 million men of military age, actually now are wanted by the police because they also evaded military registration, they avoided being called to the military service.

In addition to this, I checked my native region, in western Ukraine, the Volyn region, which is very close to Poland and there is a Telegram group of people who watch daily announcements about military conscription offices, their location and what they do, in which places they wait and try to capture the men for the military service. This group now has almost 40,000 members – subscribers. So, this is just information, basically, this means if you look into some possible number of people who are eligible for military service now in this region, this would mean that at least 25% of the people, men who are eligible for military service, actually try to escape and avoid the call for service in this region. Now consider a portion of people [from that region] who are not subscribed to this Telegram channel but watch and read without subscribing, and/or people who may be doing this as part of their families, now it's very likely that that's the absolute majority of people. And men in western Ukraine actually do not want to be captured and brought to the front line. I think this is much more significant evidence of the actual opinion of Ukrainians compared to what we see in the media and public opinion polls, which are not representative because they are very biased and unreliable.

I have a new book that will be published soon, which is an open-access book in which I also examine this issue, specifically, the evidence of a real public opinion and not what is actually presented in the media, concerning Ukrainian men and Ukrainians wanting to fight Russia until the last Ukrainian. This [sentiment] is a view that is expressed by Western politicians. They often kind of use Ukraine just to fight Russia to the last Ukrainian and this is very unfortunate a situation because it leads to significant casualties in Ukraine which has a devastating effect on Ukraine.

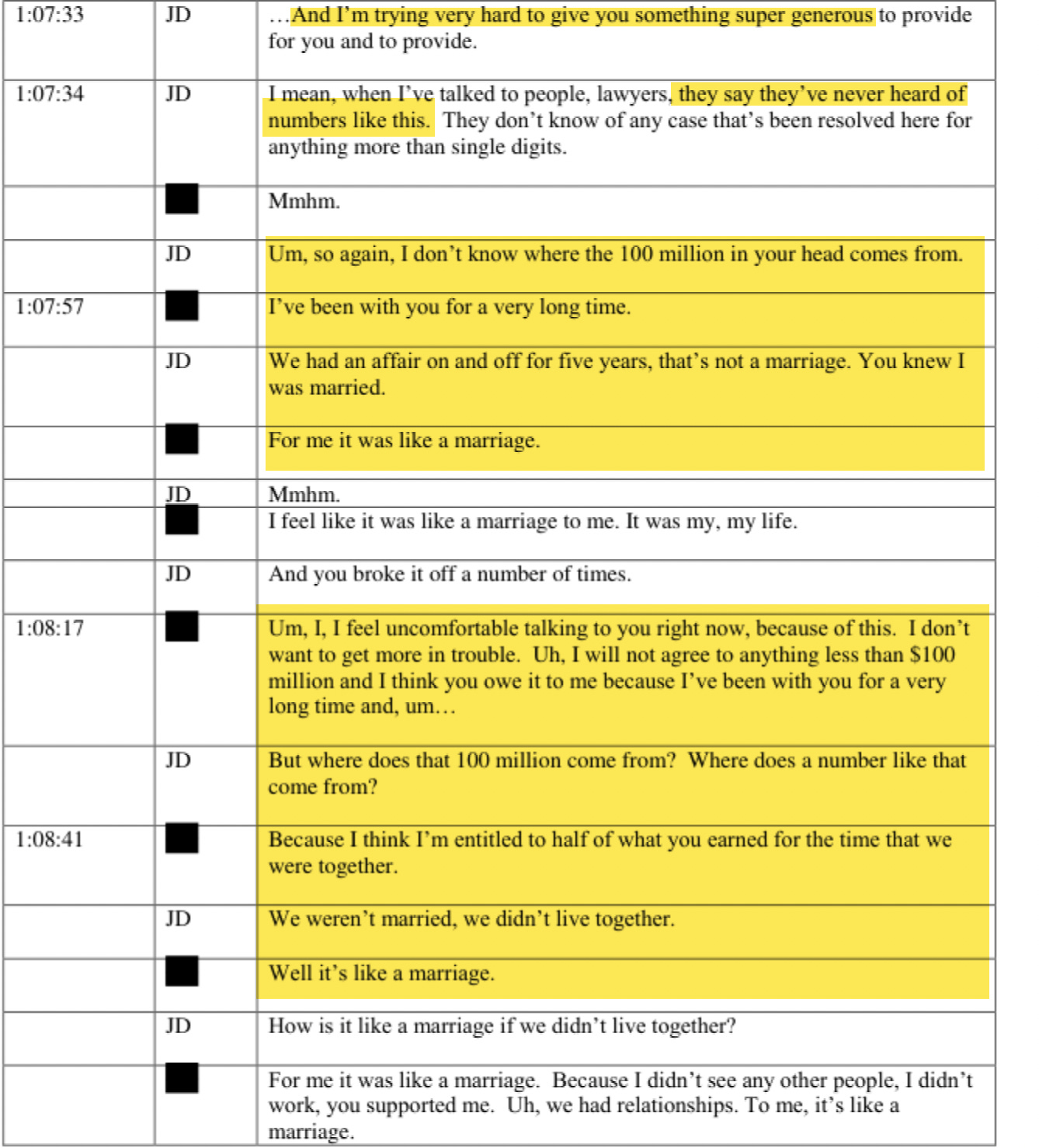

G. Greenwald: One of the things that amaze me is there's been a lot of reports, even in the Western media, about the political difficulties Zelenskyy had on expanding the draft mobilization law. The age of the draft had been 27, and he lowered it to 25. And even that was very difficult to pass. It had a lot of political resistance. And then you had an American senator, Lindsey Graham, who's been a very vehement supporter of the war in Ukraine and pretty much a vehement supporter of every war that has ever existed, who went to Ukraine and then came back and he said he was shocked to learn that the draft age was only 27 and then moved to 25. Now it kind of scares me that someone so involved in talking about the war and governing the war in the United States didn't know what you would know even just from reading Basic Report. But I think one of the things he was reacting to is that during Vietnam and other American wars, the draft age in the United States was 18. So, we were sending 18, 19, and 20-year-old kids over to fight in Vietnam and other wars before that, where the draft was used. Why has the draft age in Ukraine not been lowered to say, 18? Why is it at 27 and now 25? Given how difficult it is for Zelenskyy to get enough people on the front line?

Prof. Katchanovski: One issue is a political difficulty, because Zelenskyy did not want damages or kind of endangering his reputation, his approval in Ukraine, because for him, basically public relations is the most important issue. So, he pays very careful attention to his image. A lot of his actions were dictated by his view of what would be beneficial to him in terms of public opinion in Ukraine and the West. So, in this case, such a change to the lower recruitment age would not be very popular in Ukraine, for this reason, Zelenskyy resisted for a long time. This changed after visits by the U.S. politicians – and also you have the Senator whom you mentioned – and they basically told Zelenskyy to lower the draft age, and he did this because Ukraine is, a client state of the U.S., and the U.S. has a lot of say and influence in terms of policy for the Ukrainian government. Oftentimes, Zelenskyy follows the U.S. policy and instructions given, as illustrated by lowering the draft age.

Another issue is that there's a very small number of people, men of this age group, eligible for military service in Ukraine because, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, there was a very significant drop in the number of children that people had. Thus, the number of people who could be eligible in this age group is much smaller compared to older generations. And, another issue is that a lot of younger people, within this age group — younger than 25 years old — also have exemptions for military service such as university students. One of these policies dictated by Zelenskyy since the start of the war was to ban all Ukrainians from the age of 18 to 60 years old from leaving Ukraine. Now, people are often eligible for military service by their age, and the men who are 18 years old and 25 years old, are and were not able to leave Ukraine. And this is just the result of the policy of Zelenskyy. There is still a possibility that because of the current situation on the front line, which has a very negative dynamic for Ukraine because of the Russian military advantage, so Zelenskyy might be forced to even lower that conscription age to much younger age groups, maybe as low as 18-year-olds.

There are a lot of people, specifically in the far-right, neo-Nazis, or Azov regiment, who are now giving interviews on Ukrainian television who call openly for Zelenskyy to lower the draft age to 18 years old. So now, they lobby to press Zelenskyy to lower the draft age. I think there is a possibility that he would be forced to do this because now, there is a very difficult situation in Ukraine and Zelenskyy will try everything to prevent this defeat, but, it will be very difficult to do because Russia has an advantage in land power and military weapons.

G. Greenwald: I Just have a couple of more questions for you. Just because we've gone for about 30 minutes, I just want to be respectful of your time. But, one of the things that seemed very clear from the start of the war was that if you looked at what the U.S. and NATO were saying and how they were defining victory, which was essentially victory means the expulsion of every single Russian troop from every inch of Ukrainian soil, including Crimea, which the Russians have annexed since 2014, in response to the change of government there that a lot of people consider to be a coup. So, you have on the one hand, the U.S. and NATO saying we're going to fight until victory, which means expelling every Russian troop from all parts of Ukraine, including Crimea, and then, obviously, you look at it from the Russian perspective, and that's something they could never allow and would never allow and would do everything possible to prevent. And it seems like there is no way out of it because the Russians aren't going to leave Ukraine, certainly not going to leave Crimea, but it seems impossible as well for the West to win the war by the standard that they've defined it. Here we are, two and a half years into this war, and we're essentially in the same position. I think one of the reasons you see NATO officials talking about escalation, allowing the bombing of U.S. weapons inside Russia, or even deploying NATO forces there is because they're petrified of suffering defeat as they define the victory. There's a peace conference coming up. What do you see until the end of the year, as the prospect of having this war end?

Prof. Katchanovski: Now, the policy of the U.S. government and other Western governments is to continue the war as long as possible because, otherwise, they would be forced to admit defeat in this conflict, which was very easy to prevent in the first place. The peace agreement – which was almost reached in Istanbul in the spring of 2022 – would have avoided such a defeat and minimized such consequences, but it was blocked by the British and U.S. administration. Specifically, the U.S. wanted to weaken Russia in this proxy war. In this case, Western officials claim the goal of Ukraine is to defeat Russia, by taking back not only Donbas but also Crimea, however, it looks like a total fantasy. And this was very clear from the start. Again, I mentioned on social media, in my media interviews, and in my academic publications that the goal of defeating Russia has close to zero chance of happening. Russia, specifically, stated that they would resort to all means, including nuclear weapons, if what they call the “integrity of Russia” would be threatened. They recognize Crimea as part of Russia even though it was annexed in 2014.

So, this would mean basically that even if Ukraine forces were able to move into Crimea and take back Crimea, this would have led to an escalation of this war and Russia using nuclear weapons. So, this means it was not very likely that such a scenario would happen. At the time, Russia had a military advantage, so again, it’s not a possible scenario that Ukraine would be able to take back Crimea. The media and politicians presented this as a realistic scenario and a lot of people believed in this. Zelensky himself also declared this as a goal of his policy. And now he's in a very dangerous situation because he has no way to retreat from this. After all, he said that a peaceful agreement now is not possible unless Ukraine takes back Crimea and Donbas.

So now there is a much more significant possibility that Zelenskyy might not be able to stay in power until the end of this year because of the growing opposition to his ruling, which, again, became very desperate, according to media reports and his public statements. He recently went against Trump calling him a loser due to his proposal of a peace plan, and for Ukraine to admit defeat with a Russian occupation of [a part of] Ukraine. He criticized Biden for not going to the Peace Summit in Switzerland. He has just now gone against China, saying the Chinese are puppets of Russia and so on. So, now, Zelenskyy is acting erratically in this path. The new peace conference, which would be held in Switzerland, later this month, is the only public relations stand. Zelenskyy just wants to show that he still has support in the West and many other countries. And in reality, [in this new peace conference] there is no possibility of real peace because the only real peaceful agreement was only realistic in March and April 2022, yet it was blocked by the Western countries.

So, I think a lot of people just lie willingly because they want to use Ukraine, to weaken and defeat Russia. Yet, a lot of people don’t actually know what’s going on and how this is impossible. This is what happens when they rely on the media, politicians, and government officials as a source of information.

So, this is what I call in my Twitter comments, – with this representation of Ukraine – as a fairy tale or a Hollywood movie with a happy ending. Simply, this is garbage in and garbage out because if you rely on such garbage information, the outcome will be garbage. So, this is what the situation is. Now, I think a lot of people recognize that they've been fed all this misinformation and disinformation by the governments and media. And it’s a very tough situation for Ukraine, for Zelenskyy, and Western governments because they either have to accept a limited defeat and reach a peaceful agreement to end this war or otherwise continue this war without any realistic possibility of defeating Russia which results in more casualties to Ukraine, and more forced mobilization. I also think Russia would be able to take even more territory of Ukraine, as a result of this conflict, if it continued. A clear choice now and since the start of the war. Now the choice is for politicians actually to admit this major mistake to minimize the damage and save a lot of Ukrainian lives.

G. Greenwald: Last question for you. One of the things that really, genuinely alarmed me as a journalist was watching how the Western media narrative about Ukraine that had existed for eight years or nine years before the Russian invasion, switched immediately and completely the minute the media sold this war in Ukraine. And it did this in a lot of ways but the most notable one was that pretty much every media outlet in the West had spent many years warning of the dangers of these very strong neo-Nazi militias inside Ukraine, like the Azov Battalion. And of course, this isn't to say that Ukraine is a Nazi country, or that all Ukrainians are Nazis. And so, of course not the truth and not the point. The concern was that these are the really armed factions inside Ukraine, that they weren't really integrated with the Ukrainian military, and that they were real neo-Nazis. They have, you know, pictures of Stefan Bandera and Nazi insignias everywhere. And after 2022, the Azov Battalion got turned into heroes. You would see all kinds of praise from the New York Times and others and Western officials embracing and heralding them. How do you see today the threat of these neo-Nazi militias or battalions inside Ukraine? And what do you make of these excuses that, “Oh, the Azov Battalion has moderated, that they integrated into the Ukrainian military, that they no longer have this dangerous Nazi ideology? What do you make of all of that?

Prof. Katchanovski: [audio issues] For me, it was just a shock to see in the media the total change in their opinion. This of Azov, which is opening now not to let unit of Ukrainian media for UK initial got and then now became a new brigade in the Ukrainian intelligence and military. So, this was kind of unbelievable. This is Orwellian. So, you see people who are openly admitting their neo-Nazi views, publicly on social media before the Russian invasion, then using neo-Nazi insignia, like, swastikas and SS symbols, and so on, becoming suddenly, heroes. They met with top officials from the U.S. government. They met with members of Congress. They met with top university officials, for instance, at Oxford University and a chancellor of Oxford University. They met with Boris Johnson, who called them heroes. Again, quite unbelievable.

Even, before the Russian invasion, the U.S. Congress passed an amendment, an actual U.S. defense bill, in which there was provision for not giving any assistance, military assistance, training, or money to the Azov Battalion because of their ideology. But now this was a total change of policy because it was motivated by political reasons. The Azovs did not change; their ideology did not change, but they became presented as a rebel force. So, this is similar to what happened with Syria when there was al-Qaedal in Syria, which suddenly became a kind of jihadist and so on. They became moderate rebels because [they were] supporting democracy and so on. A similar situation happened in Kosovo during a kind of war between NATO and Serbia over Kosovo, in 1998. Suddenly, overnight, Kosovo’s liberation army transformed from a terrorist organization into an organization that was supporting freedom and so on. Mujahideen in Afghanistan during the Soviet war in Afghanistan were also presented basically as freedom fighters and so on. So, this is just pure politics, motivated by the desire to use Ukraine and now open neo-Nazis supported by Western governments. This is a very dangerous situation in Ukraine. They are a real power in Ukraine because often, even if they are numerically small, they do not have representation in Ukraine's parliament or government – there are not Nazis in the government as Russia claims – but far-right, including open neo-Nazis had a very significant role in oversight of the coalition government in 2014 as a result of this Maidan massacre. I just submitted my book today about this event and what happened during that time. So, they had and continue to have a very important role in the environment of installing a coalition government, specifically by Maidanian people, supporters, and police, who blamed the government of Yanukovich, and afterward, they became very powerful because of a reliance on force. Zelenskyy was elected as president of Ukraine, he promised a peaceful resolution of the war in Donbas, which was a civil war, with Russian support and intervention, but then, two things happened. One, far-right, basically neo-Nazi, the Azov told Zelenskyy that they will not retreat the front line. They said to him that if he wanted his peaceful agreement, he basically would be killed in Kiev. They didn’t face any punishment and they were openly kind of supported by Zelenskyy. So, Zelenskyy openly started to support them, placate them, give them support money, say they are moderates, give them medals, titles, and so on. So, this is now a dangerous situation because the far-right in Ukraine is a real opposition, a real power, and they can overthrow Zelenskyy because they rely on violence. They have military support and forces. They have an integrated community with security forces and the police. They have a lot of power. They can overthrow Zelenskyy using violence if he tries to reach this peace deal. So, in this case, I think this is an important danger for Ukraine from the far-right. In this case, Western governments and media are using this far right for their own benefit, but they can suffer blowback. Similar to what happened with Al-Qaeda [in Afghanistan], which was initially supported as part of the Taliban, supported Mujahideen, with the war with the Soviet Union, but then they launched 9/11 in the United States. Just like this, the far-right and neo-Nazis in Ukraine are dangerous because they have their military units so they can use violence not only in Ukraine but also in other countries, including the Western countries. They will be very bitter against the U.S. and many other Western governments for not defeating Russia and meeting their main goal. This is a dangerous situation for Ukraine, but also for the West. Dictated by political reasons to whitewash far-right including openly neo-Nazis, the media, and politicians tell the people otherwise.

G. Greenwald: Well, Professor Katchanovski, I think people can now understand why I consider you to be such an important source of information and knowledge and scholarship about this war. We're going to put your Twitter account in the notes to the show, so hopefully, people can follow you there. I appreciate your taking the time not just to talk to us, but to shed so much light on this area in which you're an actual expert and we'd love to have you back on soon. Thanks very much.

Prof. Katchanovski: Thank you.

G. Greenwald: All right. Goodnight.

So that concludes our show for this evening.