Welcome to a new year of System Update!

We’re back with another Weekly Update to give you every link to all of Glenn’s best moments from Monday (February 17th) to Friday (February 21st). There are a couple important updates this week that we’re sharing in this edition, so scroll down if you’ve already seen it all. Let’s get to it.

Daily Updates

MONDAY: President’s Day Holiday — No Show!

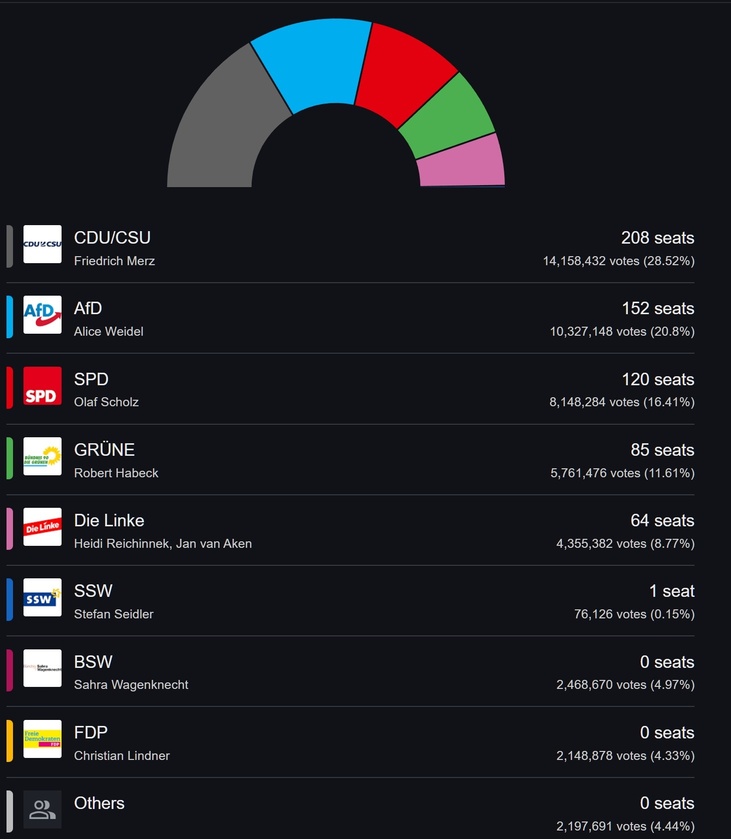

TUESDAY: German Authoritarianism & Rapprochement with Russia

In this episode, we discussed…

Germany’s repressive free speech crackdowns;

Restored communication between the United States and Russia;

A tellingly buried Florida hate crime;

WEDNESDAY: Rumble Sues Brazil as the DC Establishment Melts Down

In this episode, we covered…

How Rumble and Trump’s media company are going to war with Brazil’s chief censor;

Washington elites freaking out over Trump’s Ukraine attitudes;

THURSDAY: Economist Ha-Joon Chang Debunks Economic Myths

In this episode, Glenn spoke with the Cambridge economist about…

The economic world order, neoliberalism, the plague of economic thinking and language, Trump’s protectionism, and China;

Here’s a transcript of the interview — we heard that some people had a difficult time understanding!

FRIDAY: Glenn Reacts to the Trump Administration’s Foreign Policy

In this episode, Glenn answers more of your questions!

SYSTEM UPDATE: Watch out this Tuesday and Wednesday for a special announcement about Glenn’s most recent EXPLOSIVE interview.

Our host has been doing some traveling for the show. This upcoming episode will be crazy!

REMINDER I: About those question submissions… They’re LIVE!

Here’s a repeat announcement for all of you:

We noticed that many of you didn’t submit recorded questions, possibly because the process was unclear. Regardless, we’re here to announce that our submission feature is now LIVE. Simply follow the Rumble Studio link included in our Tuesday and Thursday Locals after-show announcements to record your questions, share praise for our editors, or comment on current events.

Again, please be aware that shorter questions are easier to include in the after-show!

REMINDER II: Locals benefits are being retooled. Here’s what that means:

For now, it means that our subscribers’ questions will be relegated to our new LIVE Friday mailbag, where Glenn will pull from the best questions, recorded and written, from the past week across all of our community-exclusive posts and discussions. Now, in other words, your questions will be seen by our entire Rumble audience. Rewards will be given for proper grammar and spelling. But there’s more!

In addition to our rescheduled question-and-answer segment(s), there will also be an increasing number of paywalled third segments, meaning that only you (our loyal Locals community members) will have access to the full range of System Update-related content. To be clear, this will happen slowly over the next month, so don’t be too alarmed. Be a little alarmed. Actually, a moderate level of alarm is appropriate—like 45% alarmed.

That’s it for this edition of the Weekly Update!

We’ll see you next week…

“Stay tuned for a Weekly Update update!”

— System Update Crew