Note to Readers: Returning to more frequent written journalism is something I have been wanting to do for some time. The combination of David's 9-month hospitalization and the need to launch our nightly Rumble show during that excruciating experience made it virtually impossible to find the time and energy for that. It is something I am still eager to do -- I'm writing an article now about the life of Daniel Ellsberg and my friendship with him for Rolling Stone, as the 92-year-old Pentagon Papers whistleblower nears the end of his spectacular life due to terminal pancreatic cancer. I originally started writing the following thoughts on grief for myself, with no intention to publish it, but decided to do so in part because I know it may give comfort to others (as the article I discuss below gave to me), but also because, for reasons I can't explain, it sometimes helps to write about this for others, and my view of the grieving process has become that you should do whatever provides any help at all to get you through the next day. I realize this is not for everyone but it's what I'm capable of and what is dominating my thoughts right now. I hope to be able to return to producing more traditional written journalism soon.

The pain, sadness, and torment of grief deepens as you move further away from the moment of the death of a loved one. It keeps getting worse – harder not easier – with each passing day and each passing week. I know that it will begin to get better or at least more manageable at some point, but that can and will happen only once the reality is internalized, a prerequisite for healing and recovery. But the internalization that someone is really dead - that there's absolutely nothing you can do to reverse that - requires ample time given its enormity. Three weeks is nowhere near sufficient.

One of the hardest challenges of grief, of the grieving process, is finding the balance between confronting the pain, loss and sometimes physically suffocating sadness – all without wallowing in it to the point that it completely consumes and then incapacitates you. But while you can't let yourself endlessly drown in it, you also can't let yourself use some mixture of distractions, work, exercise and other "return-to-normal" activities to remain in a state of denial or escapism, to avoid the pain and suffering, to deny the need to process a reality this immense and horrible, to anesthetize yourself from the mourning. The pain and suffering is going to come sooner or later, and the longer you evade or postpone it, the more damage it will do.

If you try to close yourself off to it entirety, to pretend it's not there, that attempt will fail. The pain and sadness will come at the worst times, when you're least prepared for it, in the most destructive form, and will find the unhealthiest expression. But if you force yourself to swim in those waters with too much frequency, for too much time, without maintaining a vibrant connection to the normalcy of life, to the people around you whom you love, and to the things you still cherish, it will paralyze and consume you - drain all your energy and life force and replace it with total darkness, mental paralysis and physical exhaustion: just a cold, inescapable sense of bottomless dread.

There's no perfect sweet spot, but every day, you have to keep trying to find the right balance between confronting and avoiding. What's most daunting is realizing how long this process of processing and acceptance will be: very possibly endless. During the first week after David's death, I told both myself and our kids that the first two weeks would be hard but not the hardest, that worse days lay ahead, once the shock begins to wear off and the inescapable reality sets in, once the ceremonies were over and everyone else moved on and want back to their lives. I knew we would then be left with nothing but the reality of this enormous loss and horrific absence, and that was when the worst days would commence.

But telling yourself that is one thing; experiencing it is something completely different. Even when you think you're momentarily safeguarded from it, it can just penetrate without warning in the sharpest ways. On Thursday, I stumbled into this Guardian article about a top-secret leak in Australia and there was a description of David in the article's second paragraph, printed below, that was the first time I saw this formulation in print. It fell so heavily and jarringly – at a moment when I wasn't prepared for it – because no matter how hard you try and how much effort you devote to it, the reality of death takes a long time to fully internalize. It's just very hard to believe that the person with whom you expected and wanted to share all of your life – decades more – is instead not coming back, ever, in the only form you know, that a person so full of life and strength and force is no more:

I don't know why that phrase packed such a punch. I've seen hundreds of articles and tributes talking about David's death. But this phrase casually indicates that he is someone of the past, with no present and no future in our world. It didn't just talk about the fact that David died but referred to him as a now-and-forever dead person. That subtlety had an impact far more painful and destabilizing than I could have anticipated. It disrupted my emotional state until I could find a way to move on to something else: the central challenge of every day.

All of this is complicated -- a lot -- by the need to find this balance not only for yourself but also for your kids, whose grieving is as intense but also different. It's at least just as hard to know how much space to give them to use distractions like entertainment, sports, friends and school to find some breathing space. There's a strong temptation to encourage them to use escapism because one so eagerly -- instinctively -- wants to see one's kids smiling and laughing rather than crying and suffering.

But their own need to feel this loss, the mourning, the sadness, the pain is just as inescapable as your own. There's no avoiding it. It's coming one way or the other, so you often find yourself in the disorienting position of watching your kids cry and show pain, and you feel a form of comfort and relief from seeing it because you know it's good and healthy and necessary that they feel that, even while you are submerged in that sharp, expansive pit in the center of your being that comes from having to watch your own children suffer.

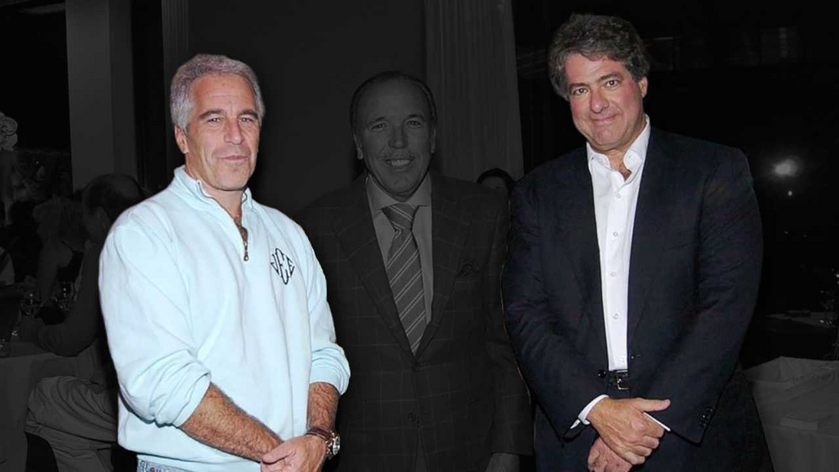

[Rio de Janeiro, March 30, 2022: four months, 1 week before David's hospitalization]

For those interested, I want to highly recommend this op-ed from last week by New York Times editor Sarah Wildman, whose 14-year-old daughter, Orli, just died after a somewhat lengthy and evidently very difficult battle with cancer. Without thinking about it, I messaged her to thank her for her article and we shared experiences, condolences and advice. One thing I did not expect was how much comfort I get from hearing from others - people I know well, people I don't know well, people I don't know at all – describe their own experiences with grief and loss. There's that old cliché that physical death is the great equalizer: the inevitable destination awaiting all of us regardless of status and station.

That is true of death, but it's also true of grief. Unless one chooses never to love in order to avoid the pain of loss – a dreary, self-destructive, even tragic calculation – the impermanence of everything material that we love means we will all experience grief and the pain of loss until we die ourselves. There's now a substantial body of research on people's end-stage regrets: what humans who know they are dying say they wish they had done more of and less of.

Virtually nobody nearing the end of life on earth says they wished they worked more or made more money (many say they regret working too much). Most say they wish they had spent more time with loved ones. When all is said and done, one of the few enduring things we really value and from which we derive meaningful pleasure - something we are built and have evolved to crave and need – is human connection. We're tribal and social animals. That's why isolation is one of the worst punishments society can impose, or that one can impose on oneself. And that's why, looking back over these last weeks and even during David's entire hospitalization, thoughts and notes and comments and kind gestures from so many people, to say nothing of those who took their time to write to me to share, often at great length, their own experience with long-term hospitalization of loved ones and profound grief, provided so much more comfort than I ever imagined it would have.

Wildman's op-ed is raw, moving and unsettling. She doesn't falsify or prettify anything for the sake of making her daughter's death more comfortable for others or herself. The death of someone you love at a young age is not pretty or comfortable. It's tragic and deeply sad and incomparably painful and there's no getting around that. Some of the best advice I got in the last couple of weeks was to avoid lionizing David or erecting a mythology around his life or around his death. I loved a human being, not a flawless saint or an icon or an otherworldly deity. And one of the things that moved me most about Wildman's op-ed was her frank discussion of her daughter's fear of dying. It would be so much more palatable - for yourself or others - to say and believe that the person you lost was at peace with dying. Her daughter wasn't at peace with dying, nor was David. They wanted to live and fought to live and were afraid to die.

That's a hard and painful truth that does sometimes make things much more difficult – it means you focus not only on what you lost, not only on what your kids lost, but on what the person who died lost – but one can also find beauty and grace and meaning and inspiration by confronting that rather than whitewashing it. It's disrespectful to someone's life to build mythologies about them - about their life and their death - no matter how comforting those mythologies might be. Wildman's op-ed refuses to do that, yet it leaves no doubt that her daughter inspired her and others not just in how she lived but in also in how she died: with her determination, courage and strength.

I blocked it out and denied it at the time because I wasn't able to accept it, but David's doctors made clear in the days after he was first hospitalized in ICU last August that the probability that he would survive the week was very low. His inflammation and infection had already incapacitated his pancreas and caused full renal failure within the first 48 hours. By the end of the week he was intubated because sepsis delivered that inflammation to his lungs. Even a quick Google search reveals how dire that state of affairs is for anyone, no matter their age or overall health.

That David fought so hard to live and return to us over nine excruciating months brought some horrifically difficult moments – watching him and his body get battered over and over every time it looked like he was possibly recovering was probably the worst thing I ever had to witness – but it also gave us and our kids some of our most moving, profound, genuine, loving and enduring moments with him and with one another that I and they will cherish forever, as I wrote about a couple months ago, in the context of gratitude, when I thought he was improving.

It may seem at first glance that had he died a quick death in that first week, David would have spared himself and us a lot of agony. That may be true. But I am absolutely convinced that had he died in that first week without giving us and himself these opportunities, all of this would be infinitely worse. Every moment you share with someone you love - even if it's in an ICU ward with every machine imaginable connected to them - is a blessing and a gift, and David's characteristic fight gave us so many of those moments that, by all rights, we never should have had.

I really wish there some singular book or some magic phrase or some way of interpreting all of this that would make the still-growing and still-deepening pain disappear for myself, for mine and David's kids, for those who loved him, for those who love and lose anyone that matters so much in their life. There is no elixir. But that does not mean that nothing helps, that one is doomed to a life of endless pain, sadness, and dread, that it is impossible to find comfort and inspiration and even greater love in the grieving process.

For that to happen, you need humility and an acceptance of what you cannot control. I can't bring David back - that's obvious - but I also can't find a way to entirely avoid the type of pain and sadness and despair that is sometimes utterly debilitating. I realized that very early on and so I'm no longer trying to avoid it entirely.

Sometimes it comes when I seek or summon it, and sometimes it comes when I think I am far away from it - like happened this week when I saw the adjective "late" before his name and on a thousand other occasions when I looked at a photo of him and his eyes connected to mine, or when one of our kids shared a memory they had of him that brought him so vividly to life. When that pain comes, I don't try to fight it or drive it away. I let it come and sometimes stay in it on purpose, until I can no longer physically endure it. Other times I allow myself to be distracted: through work, though entertainment, through proximity to my kids, through conversations with them that are not directly about sharing our mutual grief over the loss of their father and of my husband.

I don't know if I returned to work too early or, instead, am sometimes succumbing too much to my desire not to work. Each day, I try to follow my instinct about what is best for me and for our kids, and to give myself a huge amount of space and forgiveness to calculate wrong and make the wrong decisions. Down every road lies sadness and even horror, but some of those paths also offer some beautiful moments of family and connection, ways to find inspiration, to embrace the spirit and passion and compassion and strength that defined David and his life.

I'm certain that one of the things that is helping most is our unified devotion to concretizing, memorializing and extending his legacy. One of David's greatest joys in life was seeing the construction and opening of the community center we built together in Jacarezinho, the community that raised him. It offers free classes in English and computers, psychological services and addiction counseling, support for animal protection and pet care, and meals for that community's homeless. We are going to create and build "The David Miranda Institute" to extend that work beyond that community. My kids are eager to assume a major role in working on this institute and community center – they know instinctively that it honors David and would make him so proud – and working on this together is one of the few things that provides us unadulterated comfort and uplifting energy.

The grieving process is horrible but not hopeless. I'd be lying if I denied that it sometimes seems unbearable. Every day the reality that David lost his life and that we lost David in our lives gets heavier and more painful. But humans are resilient. We are adaptive. I can't prove it and there was a time in my life when I not only rejected but mocked this idea, but I believe our life has a purpose and, ultimately, so do our deaths. Each day I see that my suffering and our kids' suffering deepen and worsen for now.

But I also see us, together, creating ways to find and remain connected to that purpose. David's life, David's spirit, David's legacy, and somehow even David's death are what is propelling us, elevating us, toward that destination. I would trade anything for David to be back with us, but since that option does not exist, getting through the pain and then finding a way to strengthen us is our overarching challenge.